Witness to History

David Hume Kennerly archive becomes a permanent collection at the Center for Creative Photography

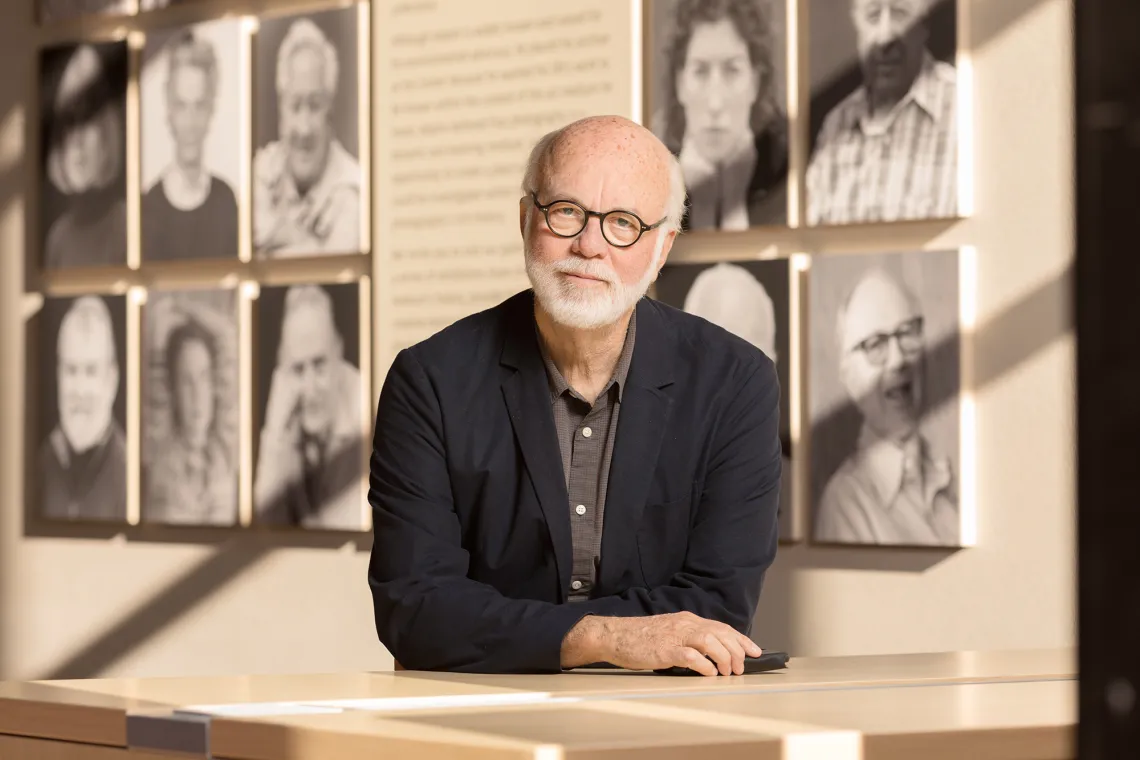

David Hume Kennerly / Chris Richards photo

David Hume Kennerly, whose photographic archive is now at the University of Arizona, won the Pulitzer Prize for feature photography when he was just 25 years old.

The day after he got the big news, he almost lost his life.

It was 1972, the height of the Vietnam War, and Kennerly was working as a combat photographer, documenting the bloody war for UPI. He had already been in the war-torn country for a year, and his battle photos had helped him win the coveted Pulitzer.

George H.W. Bush, George W. Bush, Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter with President-elect Barack Obama two weeks before Obama’s inauguration, in the Oval Office, 2009. Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona: David Hume Kennerly Archive

He didn’t have much time to celebrate. The next day, when Kennerly and a UPI colleague drove 25 miles north of Saigon, they suddenly found themselves in the middle of a deadly firefight.

Viet Cong soldiers were on one side of the road, and South Vietnamese — and a couple of American military advisers — were on the other. Bullets were flying.

“We came under fire from the North Vietnamese,” says Kennerly, now 72 and still an active photographer. “It was raining. We couldn’t get air support. Twelve soldiers were gunned down.”

But Kennerly didn’t run for cover. “I was trying to take pictures,” he says. “Doing what I do.”

During those terrifying moments when the bullets whizzed past him,

he imagined his friends getting the news of his death.

But he didn’t die that day. Their driver managed to get the two photographers out.

Ever since, Kennerly says, he’s been grateful. “I escaped death. I was alive, I got the Pulitzer Prize,” he says, then pauses.

“Every day is a gift.”

Kennerly has used that gift of life to forge an extraordinary career.

It began when he was quite young. He scored his first published photo as a teen in 1962, when he made what he laughingly calls a “mediocre baseball shot” for his school newspaper in small-town Oregon; from there, it was a quick jump to local newspapers and then to the national press.

And he’s still going. Last summer, at age 72, he covered the Robert Mueller hearings for CNN.

In the long years between those two photo shoots, Kennerly used his camera to capture every president from Nixon to Trump, to photograph in 130 countries, and to publish his work in news outlets from Life to CNN and from Time to Newsweek, where he’s scored dozens of cover photos.

Justices Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, first and second women to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court, in the Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol, 2001. / Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona: David Hume Kennerly Archive

His photos are a chronicle of contemporary history. His expertly crafted images document wars in Cambodia and Vietnam, the Watergate scandal, the Robert Kennedy assassination, President Reagan’s meeting with Mikhail Gorbachev, President Clinton’s impeachment and the 2016 elections. In sports, Kennerly captured the Mets’ World Series win in 1969 and the 1971 boxing match between Mohammed Ali and Joe Frazier.

Now, Kennerly has permanently placed his archive in the Center for Creative Photography at the UA. Students, faculty and the general public will have access to not only the Vietnam images that helped him win his Pulitzer but also the thousands of other photos he made portraying signature world events.

“It’s the right place for the archive to be,” he says. “This is an institution that will care for it. The work encompasses history, art, journalism and the history of photography. That’s why it’s at a university — it needs to be seen and studied.”

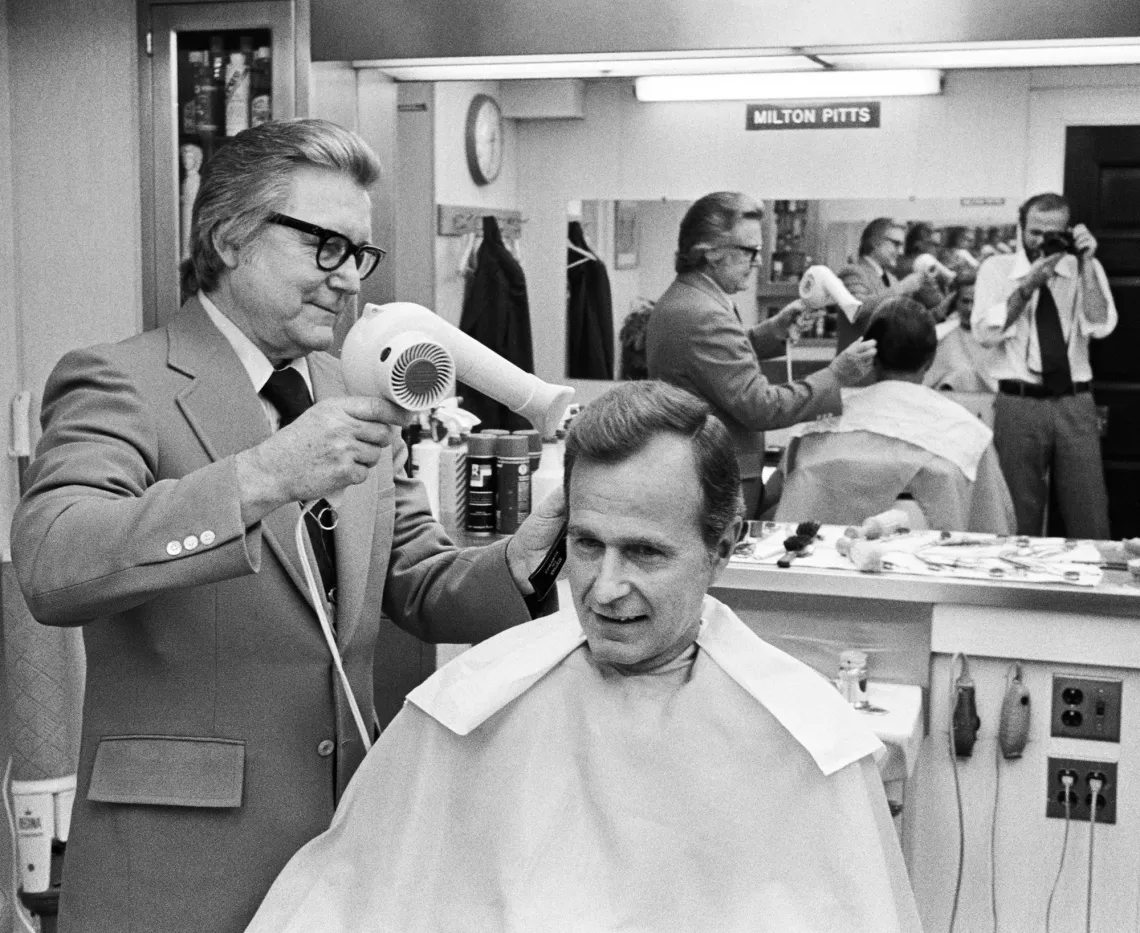

CIA Director George H.W. Bush with White House barber Milton Pitts, in the West Wing of the White House, Washington, D.C., 1976. / Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona: David Hume Kennerly Archive

He chose the UA over other universities that were courting him in part because CCP Curator Rebecca Senf “was dogged in her pursuit” and UA President Robert C. Robbins “really wanted it to happen.” Kennerly also was moved by personal ties. Ansel Adams, who cofounded the CCP, was a friend, and Kennerly got his first Time cover with a portrait of the great photographer.

In honor of the university’s new Kennerly connection, an exhibition of his work has been mounted at Old Main. The show, running indefinitely, includes plenty of his Arizona images.

“I love Tucson,” he says, “and I have a lot of Arizona connections.”

In 1968, he came to the UA to cover a Robert Kennedy campaign stop. Over the years, he photographed Arizonan Sandra Day O’Connor, first female justice on the Supreme Court, and the young Linda Ronstadt. He photographed Sen. John McCain so often that the family appointed Kennerly the official photographer for McCain’s funeral in 2018.

Kennerly also has been named the university’s first Presidential Scholar, a role that will have him participating in classroom meetings with students and professors and bringing renowned figures in journalism and politics to campus.

Looking back over his long career, Kennerly remembers an early inspiration. As a kid, he saw reporters rush to a fire in his neighborhood. He was impressed that they were able to go right behind the police line. “They had access to the action.”

President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev at the first American-Soviet Summit, Geneva, Switzerland, 1985. / Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona: David Hume Kennerly Archive

His career has brought him astonishing access. In Vietnam, he was in the jungles with soldiers. In Washington, D.C., at the age of 21, he found himself flying in Air Force One in the Nixon press pool. And when Nixon resigned in disgrace, his successor, Gerald Ford, offered Kennerly — then 27 — the job of presidential photographer. Kennerly said he would accept on condition that he have total access to the president, no restrictions.

“I was pretty bold to ask, but Ford agreed,” says Kennerly.

The young photographer had an inside seat watching Ford, who, he says, was a remarkably decent man: honest, fair and respectful to all.

“He never intervened in my photos. It was intense and deeply satisfying. I had a free hand to document a presidency.”

The exhibition “David Hume Kennerly: Witness to History” will remain on view indefinitely at Old Main on the UA campus.

Former President Gerald R. Ford lies in state in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, Washington, D.C., 2006. / Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona: David Hume Kennerly Archive