Big Vision

A look at John Schaefer’s multifaceted legacy.

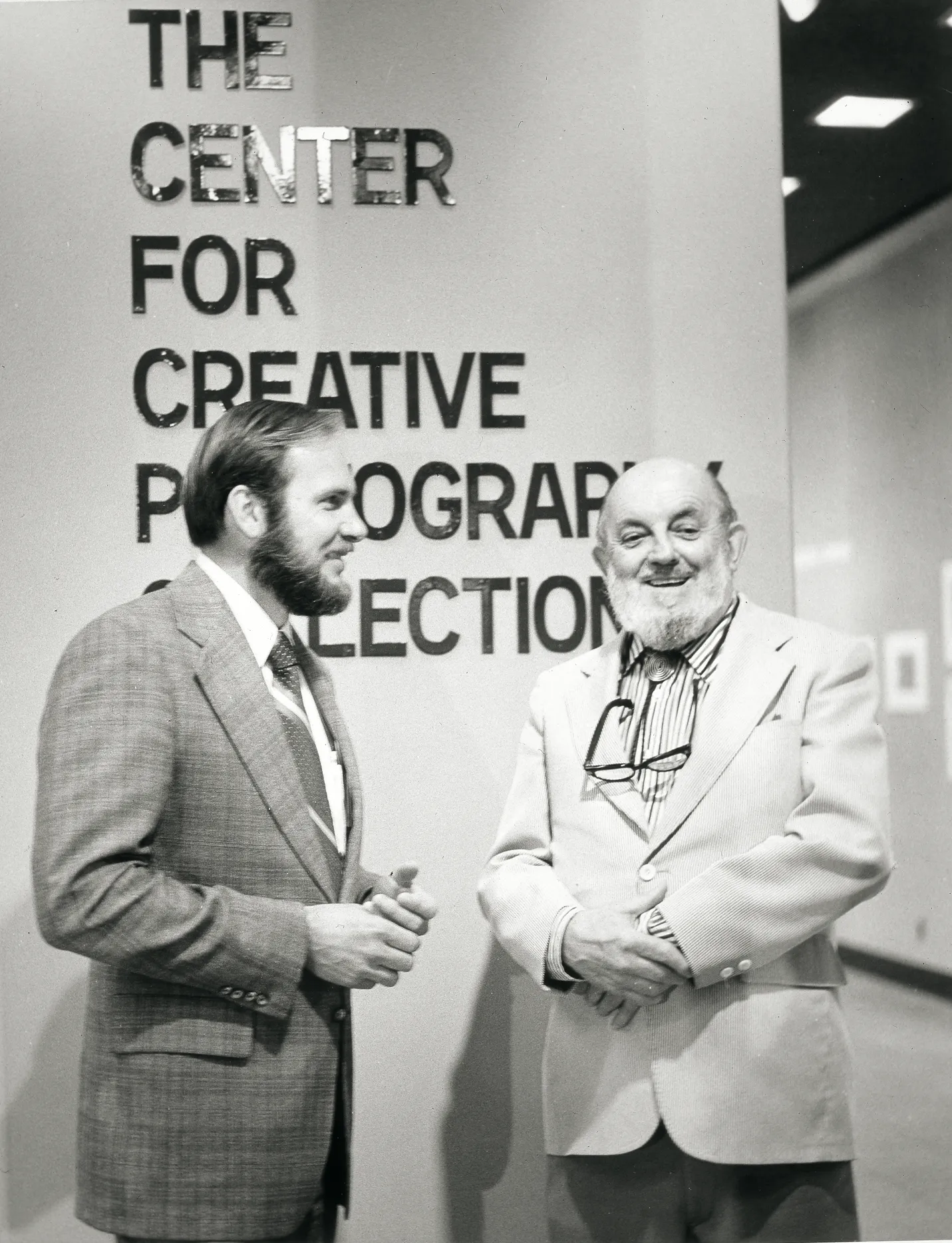

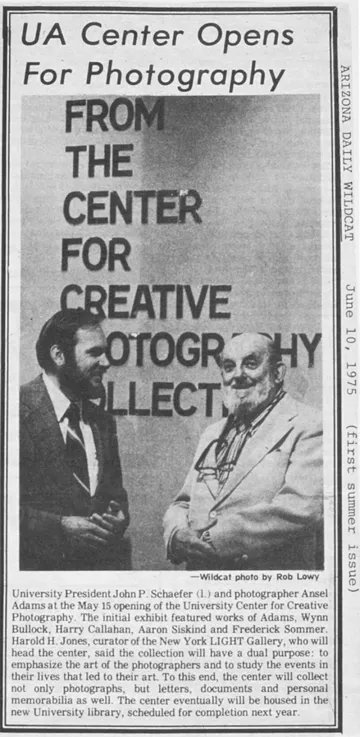

Dr. John P. Schaefer and Ansel Adams at opening exhibition of the CCP, 1975, AG 1.

Center for Creative Photography archive, The University of Arizona, Tucson

When then-University of Arizona President John Schaefer approached Ansel Adams about housing Adams’ archives at the U of A, he wasn’t just indulging an interest in photography — he was seeing an opportunity. Schools like Harvard and Yale had their world-class libraries; they also had a couple hundred years’ head start on building them. But with a few exceptions — including the Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin — no major university had come to recognize the power and significance of photography either as an art form or as a means of historical documentation.

This was 1974. Schaefer was just shy of 40 — the second-youngest president in the university’s history. Within a year, the Center for Creative Photography was born, and with it, the growing sense of the U of A as a place where exceptional things might happen.

“Photos really changed history,” Schaefer says, reflecting on the eve of the center’s 50th anniversary. “Child labor laws disappeared because of photographs at the turn of the century of 8-year-old kids working on machines and getting hurt. We became sensitized to immigration issues with the photographs of Jacob Riis on the Bowery at the turn of the last century. The war in Vietnam ended because of photography. I believe people got sick and tired of seeing pictures of what was going on there, day after day, night after night.”

The CCP is only one facet of Schaefer’s legacy. A former chemistry professor, he helped the university in its push to secure its designation as a Research 1 institution and gave early and crucial support to projects like the Mirror Lab, then a hodgepodge of scientists housed in some unused space under the football stadium but soon to be a major force in optical science and tele-scope design.

“Arizona suffered from the fact that although we had a good astronomy department, we had no real large telescope to compete,” he says. U of A optical sciences center founder Aden Meinel had the then-radical idea to arrange a group of six smaller mirrors hexagonally to make the equivalent of a single large one.

Schaefer remembers approaching the National Science Foundation for funding and getting shot down on the grounds that it wouldn’t work. “That turned out to be wrong,” he says, matter-of-factly but with a smile. “We turned out to be right. And that became the paradigm for every large telescope that’s been built since.”

He also maintained a healthy photographic practice of his own, including images of the Mission San Xavier del Bac published in Arizona Highways in the late ’70s and a small collection kept at the CCP. “When I became an administrator, I decided I really needed an outside interest to stop from going crazy,” he says. That was more than 50 years ago. He published his most recent book — “Desert Jewels,” a collection of cactus flowers — in 2023, at the age of 88.

Of all his achievements, Schaefer has said that few have made him as proud as getting the university to buy into the idea that it could be as good as any school in the country. Talking to the U of A’s Archive Tucson project in 2017, he said, “For a long time, I think one of the real challenges at Arizona was that we didn’t realize how good we were.”