Louis Carlos Bernal: Retrospectiva

An exhibition at the Center for Creative Photography showcases scenes from Mexican American life by one of Tucson’s greatest artists, Sept. 14-March 15, 2025.

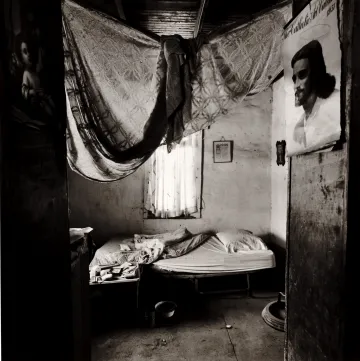

Louis Carlos Bernal, 4th Street Barrio, Douglas, 1979, Center for Creative Photography, the University of Arizona: Louis Carlos Bernal Archive.

© Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Ann

The story has been told often. On a day in 1977, the artist Louis Carlos Bernal went out for a walk in Tucson’s Barrio Viejo. As always, he had a camera in hand. The neighborhood of corner grocery stores and rows of modest houses had once been the thriving hub of the city’s Mexican American district. But it had gotten a lot smaller 10 years earlier, when the city destroyed some 263 buildings and pushed more than 300 families out.

As he walked, he found a house with its front door slightly open. He called out to see if any-one was home and then peeked in. All he could see was layers of dust on the furniture. Realizing that no one was living there anymore, he came back the next day, eager to take pictures.

Louis Carlos Bernal, Calendario, 1977, Center for Creative Photography, the University of Arizona: Louis Carlos Bernal Archive.

© Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Ann Bernal.

On a dresser, he found a glorious collage of objects: a statue of the Infant Jesus of Prague, a picture of Pope Pius XII and dried flowers in a Folgers coffee jar. He took a photo, now called “Pope Pius XII.” Another, “Ahora,” captured a pile of handwritten notes in Spanish, some with prayers, some a short list of groceries. In their midst was an image of a victorious St. Michael in the throes of destroying the devil. In “Calendario,” a canopy of cloth drapes from the ceiling with a painted Jesus looking down lovingly above a simple folding bed.

Bernal eventually tracked down an old woman who had lived there, Mary Benitez. “I went to see her and showed her the photographs that I had done of this house,” Bernal remembered some years later. “And she was very excited. … She gave me permission to do the photographs.”

These marvelous photos were given the name “Benitez Suite.” Seven of these works are included in the first large retrospective of his life’s work, the “Louis Carlos Bernal: Retrospectiva” at the Center for Creative Photography. Thanks to Bernal’s daughters, Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Bernal, the CCP is the permanent home for much of his archive. These loving pictures are among 125 photographs in the exhibit that record the life of Mexican American communities at the end of the last century.

Elizabeth Ferrer, curator of the exhibition and a specialist in the history of Latinx photography, is the author of the show’s companion publication, “Louis Carlos Bernal: Monografía,” to be co-published by CCP and Aperture. She believes that Bernal experienced “an apotheosis of sorts” when capturing the images of the Benitez Suite. “What he saw in the barrio changed him.”

In an interview with Arizona Illustrated in 1982, Bernal himself said, “I was looking for an identity in images. And this is what I found, only it was lusher, much richer and more in-tense than I ever anticipated it would be. … And as a photographer and as a Chicano, I feel I have an obligation to my community to photograph and reproduce images that deal with the culture.”

Louis Carlos Bernal, Cholos, Logan Heights, San Diego, 1980, Center for Creative Photography, the University of Arizona: Louis Carlos Bernal Archive.

© Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Ann

Bernal first took to photography when he was 11, after an aunt gave him a camera. After that, he never was without one. He went to college at Arizona State University and eventually earned a master of fine arts there. He also studied with Frederick Sommer, an internationally known photographer based in Prescott whose archive also is at the CCP. In 1972, Bernal landed a coveted teaching job at Pima Community College. He loved it and worked there for the rest of his life.

Despite his successes, Bernal struggled financially. A breakthrough came in 1977, the year that he made the Benitez Suite. He was invited to contribute to “Espejo: Reflections of the Mexican American,” a touring show funded by the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund. Ferrer points out that the support enabled Bernal to work in color much more than he had before. Until then, most of his photographs had been in black and white.

His work began to be shown around the country and, eventually, in Mexico.

The next year, he returned to his childhood home of Douglas, Arizona, to take photographs in the homes of relatives and friends. One of his most famous photos from that time, “Dos Mujeres, Douglas, Arizona” shows two young women sitting in adjacent rooms. Both are looking directly at Bernal. The living room is painted a rich blue-green; the nearby bedroom is painted a vivid pink. The girl in the foreground is doing needlework, while the other is combing her hair. Golden southwest light pours through a window, illuminating each of their beautiful faces.

In another Douglas color photo, “Barrio Portrait, H Avenue Cuadra,” three children stand outside a red brick home on a chilly winter day, their young parents watching adoringly from the front door. Two trees, stripped of their leaves, frame the portrait. The colors are chestnut brown and autumnal tan and red. The children stare directly at the camera, looking shy but curious.

Over the next decade, Bernal created several series of photographs of hard-working people in barrios elsewhere in the southwest. In Lubbock, Texas, he took a striking black-and-white portrait of a baker, José Padilla, called “Panadero.” Padilla stands surrounded by his pastries — pan dulce, garra de oso, empanadas — looking exhausted. In an untitled photo from Lubbock, an older couple stand in a yard of zinnias and prickly pear, holding a basket of fresh-picked fruit.

In the early 1980s, Bernal also went to Mexico multiple times. As a young man, he had studied Spanish in Mexico City. He had his beloved camera with him, and, in 1962, he exhibited photographs there for the first time. In one of these early pictures, “Chiclets, Cuernavaca,” a charming barefoot boy stands with a smile and a box of Chiclets to sell to passersby. It’s the earliest of Bernal’s photographs in the CCP show.

Louis Carlos Bernal, Martinez Brothers in Candy Store, Douglas, Arizona, 1978, Center for Creative Photography, the University of Arizona: Gift of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund.

© Lisa Bernal Brethour and Katrina Ann Bernal.

In 1981, Bernal was invited to show some of his work and participate in the Segundo Colo-quio Latinamericano de Fotografía, an international conference held in the grand Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. Ferrer says, “He developed a wide circle of friends who were then Mexico’s leading photographers,” including Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Lola Álvarez Bravo and Graciela Iturbide, all three of whom also have collections at CCP.

“He was respected by them,” Ferrer writes, “and treated as an equal. This was not the case in the U.S., where he felt marginalized.”

Nonetheless, he was very busy in those years. He had a group exhibition in Germany, workshops in several cities including Havana, Cuba, and group shows in California, and, of all things, was invited by the Los Angeles Olympic Committee and took photos behind the scenes.

It all came to a stop on Aug. 21, 1989. Bernal was hit by a car as he was riding his bike to work at Pima. He was left in a coma and never recovered. Four years later, he died on Aug. 18, 1993, at age 52.

His good friend and colleague at Pima, Ann Simmons-Myers has been devoted to keeping his work in the public eye. “Retrospectiva” is the happy culmination of her partnership with the CCP and Bernal’s daughters, long awaited by his many friends and admirers.

Thank you to the Henry Luce Foundation for support of this exhibition.