Qualities of LIGHT

Installation view: “The Qualities of LIGHT: The Story of a Pioneering New York City Photography Gallery.” Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona. / Chris Richards photo

When Rebecca Senf began doing research for a show about LIGHT, the pioneering photography gallery in New York, she pored over the lists of photographers she might interview.

LIGHT ran from 1971 to 1987 — “a pivotal time for photography,” she says — and she wanted to get the story right.

Senf, curator of the University of Arizona’s Center for Creative Photography, would go on to speak to dozens of people for “The Qualities of LIGHT: The Story of a Pioneering New York City Photography Gallery.” But the first interview she did, with acclaimed photographer Jerry Spagnoli, made clear from the start the reasons that LIGHT matters to the history of photography.

“Jerry was a young student when LIGHT opened,” Senf says. He already knew he wanted to be a fine art photographer — though his parents thought that meant being a wedding shutterbug — but “there was not a lot of information about photography then. This was before the photography book boom. There was no internet.”

Worse, there were few places to see photos: The art world had not yet fully accepted photography as a legitimate art form.

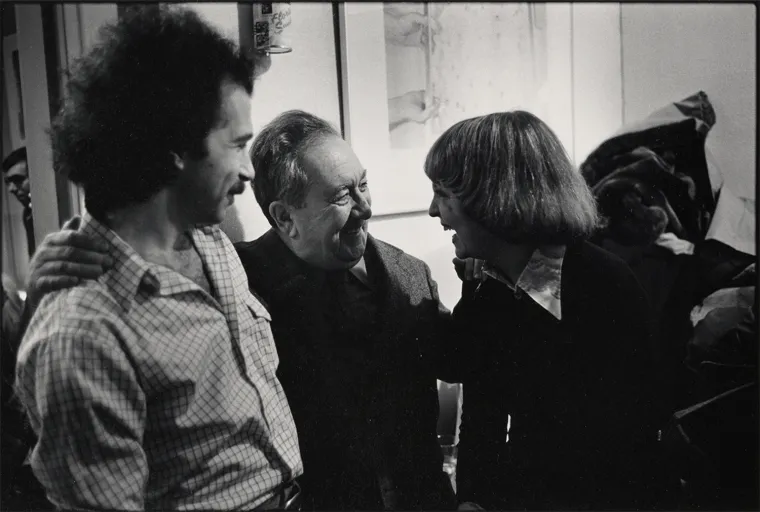

BD Vidibor, Aaron Siskind, Diana Edkins. | BD Vidibor, 1018 Madison Ave. Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: LIGHT Gallery Archive. © BD Vidibor

BD Vidibor, Aaron Siskind, Diana Edkins. | BD Vidibor, 1018 Madison Ave. Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: LIGHT Gallery Archive. © BD Vidibor

But Spagnoli discovered LIGHT, a gallery that took the bold step of exhibiting contemporary photography. There, he could not only see photos by established artists like Ansel Adams, Harry Callahan and Paul Strand but also immerse himself in the experimental work of young, not-yet-famous photographers: Garry Winogrand’s exhilarating street shots of New Yorkers; Emmet Gowin’s intimate images of his family; Linda Connor’s stirring photos of religious sites around the world.

At LIGHT’s legendary openings (said to have drawn stars like Patti Smith, Robert Mapplethorpe and the Warhol gang), the aspiring young photographer could even meet these working photographers.

And he watched LIGHT sell their work, expanding the market for the older artists and launching the younger ones.

The gallery changed Spagnoli’s life. “LIGHT illustrated for him that a career in photography was possible,” Senf says.

And Spagnoli was not the only one. LIGHT influenced a generation of young artists and academics and propelled them into careers. In just 16 years, LIGHT also seeded influential galleries. Young staffers who worked at LIGHT went on to run four of New York’s major galleries, including Pace/MacGill and Robert Mann. And, perhaps most importantly, LIGHT won the battle to recognize photography as an art form.

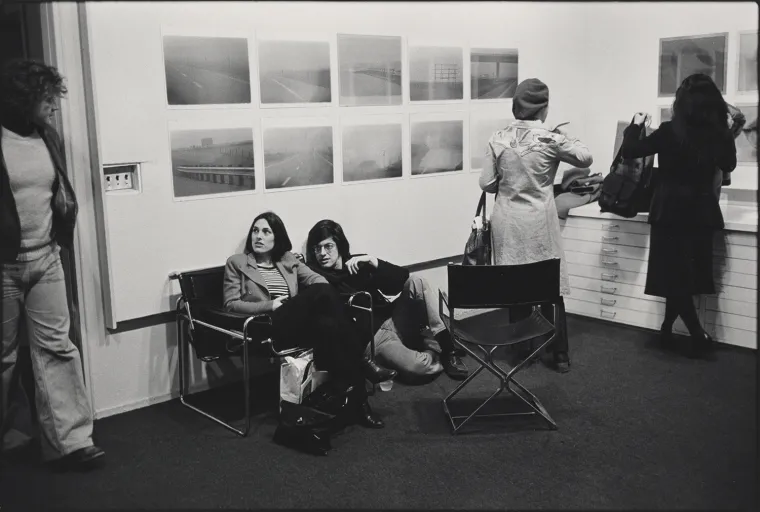

Installation view: “The Qualities of LIGHT: The Story of a Pioneering New York City Photography Gallery.” Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona. / Chris Richards photo

“The Qualities of LIGHT” takes a different approach than most CCP exhibitions. Shows usually focus on a particular photographer, but the exhibition is instead an intensive look at one gallery and its influence.

The rooms are filled with entertaining photos of celebrities at LIGHT parties (see if you can find photog André Kertész smiling over his birthday cake circa 1974). There are works by artists who today continue the gallery’s spirit of experimentation, including Arizona-born Lilly McElroy and Eric Pickersgill, who contributes a classic black-and-white of a young couple staring blankly into their empty hands, with no cellphones in sight.

One room is filled with photos dating to the LIGHT years, created by some 20 LIGHT artists. Harry Callahan, often associated with images of wintry Chicago, here checks in with stark photos from 1974 of sunlit houses in Cuzco, Peru. Ray Metzker, the same year, was changing dark cityscapes in Philadelphia into abstractions.

“LIGHT’s contribution to photography is unmatched,” CCP director Anne Breckenridge Barrett says, and the CCP is the perfect place for the exhibition. It not only holds the LIGHT archives but also is home to the archives of many LIGHT alumni, Callahan included.

Aaron Siskind: Arizona. 1949. Gelatin silver print, 19.1 x 34.3 cm. | Ikko Narahara: Japanesque #53, Sojiji, Japan. 1969. Gelatin silver print, 8 13/16 x 13 in.

Aaron Siskind: Arizona. 1949. Gelatin silver print, 19.1 x 34.3 cm. | Ikko Narahara: Japanesque #53, Sojiji, Japan. 1969. Gelatin silver print, 8 13/16 x 13 in.

Plus, there’s a University of Arizona connection. Harold Jones, LIGHT’s first director, left the gallery in 1975 to come to Arizona, where he was the founding director of the CCP and created the university’s photography program.

Now an emeritus professor after 30 years of teaching, Jones is approaching his 80th birthday. The CCP had been pondering a way to honor his many contributions to the university and to the field when Barrett hit on the idea of a show about LIGHT.

“Harold was only at LIGHT four years, but he set a tone,” Senf says. “The gallery was experimental, fearless and idealistic. It took risks. Harold was not primarily focused on the bottom line. And he was incredibly loyal to the photographers.”

Jones studied both art history and studio photography at the University of New Mexico. After he got a job as assistant curator at the George Eastman photography museum, he was quickly lured away by Tennyson Schad, the lawyer who created LIGHT.

Schad had in mind a gallery devoted to documentary photography, but Jones persuaded him to gamble on presenting contemporary, experimental work.

“Harold always saw the potential to educate,” Senf says. “LIGHT acted like a school.” And eventually, thanks to Jones, “LIGHT Gallery played a critical role in photography’s legitimization.”

Lilly McElroy: I Control the Sun #18. 2016. Archival pigment print. Courtesy of the artist and Rick Wester Fine Art. © Lilly McElroy

In the pioneering spirit of LIGHT, the CCP team is using the latest technology to tell the gallery’s story. For the first time, the center has created an app to go with an exhibition. Available as a phone app or online, CCP Interactive is full of photos from the show and commentary from Senf.

“This allows us to share the content in a way we’ve never done before,” she says. “People anywhere can see the images and listen to the narration.”

But still it’s the art that matters most. Asked to pick favorites from the exhibition, Senf hesitates. She loves the photos by the up-and-coming photographers in the show, but she also loves the innovative LIGHT photos from the 1970s.

One favorite photographer is the late William Larson, a Philadelphia artist who showed at LIGHT and spent time in Tucson. In a 1970s color photo of a Tucson yard, Senf says,

“He captures the way sunlight creates washed-out color,” and makes the landscape otherworldly.