Wonder Makes Us Explore

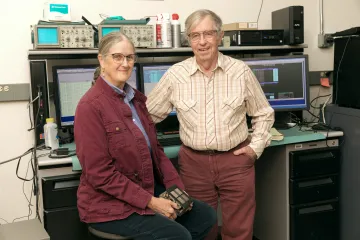

Marcia Rieke | 160/90 Photo

Whenever Marcia Rieke points her telescope into her favorite part of the night sky, she looks toward the constellation Sagittarius. What she is looking for is, well, nothing. A void. In that absence of light is a supermassive black hole — our galactic center.

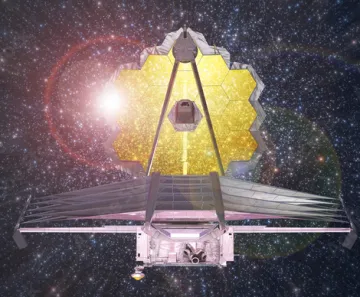

While you are reading this, the James Webb Space Telescope is orbiting the sun, having successfully launched, deployed from its rocket and traveled one million miles from Earth over the period of 30 days. It has taken its first image.

It only took 20 years to get to this point.

But when Arizona Alumni Magazine interviewed Rieke in October 2021, she told us, “As we speak, they’re probably taking the telescope off the ship.” It had just completed a 16-day journey at sea, landing in French Guiana. This July, after the deployment sequence is complete and everything is aligned and calibrated, Rieke’s team can start observing.

“I’m kind of all over the place,” jokes Rieke when asked where she wants to point the Webb telescope. “I want to find the very first galaxies and understand how galaxies have changed over time since they formed.”

After Hubble, scientists wanted a greater telescope for infrared astronomy, specifically to look at the earliest galaxies. In all our space exploration, we have yet to see those first galaxies and stars of the universe, which formed about 100 to 250 million years after the Big Bang. These objects are so distant that their light shifts into red wavelengths our eyes can’t see.

That is what the Webb Space Telescope’s Near Infrared Camera, or NIRCam, is designed to capture. “We’re spending almost half of our 900 [observation hours during the Webb telescope’s first year] looking for the most distant galaxies,” says Rieke, NIRCam’s principal investigator.

Rieke first became involved with the Webb telescope in 1998, when NASA convened an ad hoc working group to outline what the mission should be. “What should the telescope look like? What kinds of scientific instruments should it have?

What were the key science goals?” Rieke says.

In 2001, she assumed the role of principal investigator for a team that included scientists from not only the University of Arizona but also Lockheed Martin, Université de Montréal, NASA Ames, Caltech and many others. Together, they won the proposal to build, test and — finally — operate the NIRCam.

“I had to translate between what the engineers were thinking and what the scientists were thinking about,” Rieke says. She was responsible for meeting requirements and making sure that that the NIRCam was feasible to build.

It was the chance to study infrared that had brought her to Arizona after she received her PhD from from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1976.

The university’s ground-based telescopes are Rieke’s favorite places to visit in Tucson. “The observers’ dormitory is kind of like a cabin in the woods,” she says of Catalina Station, home to the Kuiper and CSS Schmidt telescopes. “In terms of ambiance, the 61-inch telescope that the university has on Mount Bigelow is a very, very pleasant place to go.”

When Rieke isn’t looking through the lens of a telescope, she’s often looking through a camera’s viewfinder. Her home and office walls are covered with her framed photography. Her Zoom background during our interview was a photo she took from her backyard of a lunar eclipse in a rose quartz sky over Mount Kimball in Tucson’s Santa Catalina range.

Besides looking for the universe’s earliest galaxies, another goal for the NIRCam will be looking at exoplanets — the thousands of planets just outside the solar system. “I’m really excited to learn about what’s in an exoplanet atmosphere, because it just seems so remarkable that not only do we now know about planets around other stars, but we can actually study their composition, in a way,” Rieke says.

“We might be able to see what kind of molecules would be in the exoplanet’s atmosphere. That’s pretty exciting, because we can potentially find an atmosphere whose composition would be like Earth’s.”

The NIRCam is one of four scientific instruments that make the Webb telescope the most powerful infrared telescope to date. Astronomers from all over the world will use the telescope. In its first year, 7,000 observation hours are planned in total. UArizona will get 900 hours as a reward for the contributions Rieke and her team made to the development of the telescope.

Data from the telescope could lead to answering questions about the origins of the universe and whether other planets in our galaxy are habitable. Are we alone? Where did we come from? Right here in Tucson, we might discover clues to the answers.

Artist conception of the James Webb Space Telescope. A tennis-court-size shield will keep the extremely sensitive infrared detection instruments out of the sun’s rays. / Adobe Stock photo

“When I was an undergraduate, infrared astronomy was not a fully formed section of astronomy yet. It wasn’t until I was a graduate student that there really was a subfield called ‘infrared astronomy.’”

Eminent astronomer and founder of the UArizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory Gerard Kuiper became interested in infrared astronomy in the 1960s. He hired Harold Johnson and Frank Low, who would become an early leader in the new field. Low and Johnson hired George Rieke, whose list of contributions to infrared technology, theory, observation and instrumentation is extensive.

George Rieke hired Marcia — then Marcia Lebofsky — for postdoctoral research. “I knew who he was, because he was one of the founding infrared astronomers. He was pretty famous already,” she says.

At Arizona, they fell in love. “We got married in Tucson at a church on the east side. For the reception, we decided we didn’t want a traditional wedding cake, so we had baklava instead.” Now married for 38 years, they work in offices about 100 feet apart. “We’ve worked together so long that though we like to talk about work in detail, we can also guess what the other one’s going to do or say.”

While Marcia and George worked together on the Spitzer Space Telescope and the Webb Space Telescope, Marcia also worked on the infrared camera on the Hubble Telescope, which might have given her the edge as a candidate to be the PI for Webb.

UArizona has remained a leader in the field of infrared astronomy since Low’s work in the 1960s. Infrared is best done where there are few water molecules to interfere with the infrared light coming to down to Earth, so Tucson’s dry climate is a boon. Beyond the climate, telescopes are what distinguish UArizona from other schools that study infrared astronomy.

The university’s ground-based telescopes are Marcia Rieke’s favorite places to visit in Tucson. “The observers’ dormitory is kind of like a cabin in the woods,” she says of Catalina Station, home to the Kuiper and CSS Schmidt telescopes. “In terms of ambiance, the 61-inch telescope that the university has on Mount Bigelow is a very, very pleasant place to go.”

Marcia and George Rieke / Chris Richards photo

When Rieke isn’t looking through the lens of a telescope, she’s often looking through a camera’s viewfinder. Her home and office walls are covered with her framed photography. Her Zoom background during our interview was a photo she took from her backyard of a lunar eclipse in a rose quartz sky over Thimble Peak in Tucson’s Santa Catalina range.

Besides looking for the universe’s earliest galaxies, another goal for the NIRCam will be looking at exoplanets — the thousands of planets just outside the solar system. “I’m really excited to learn about what’s in an exoplanet atmosphere, because it just seems so remarkable that not only do we now know about planets around other stars, but we can actually study their composition, in a way,” Rieke says.

The NIRCam is one of four scientific instruments that make the Webb telescope the most powerful infrared telescope to date. Astronomers from all over the world will use the telescope. In its first year, 7,000 observation hours are planned in total.

UArizona will get 900 hours as a reward for the contributions Rieke and her team made to the development of the telescope.

Data from the telescope could lead to answering questions about the origins of the universe and whether other planets in our galaxy are habitable. Are we alone? Where did we come from? Right here in Tucson, we might discover clues to the answers.

Marcia Rieke is a University of Arizona Regents' Professor of Astronomy, Astronomer and Elizabeth Roemer Endowed Chair, Steward Observatory.