Be the Ripple

A teacher and first-generation college graduate reflects on his time at the U of A. As told to Arizona Alumni by Jonatan Noriega ’17 ’19.

When I was in 8th grade, my teacher Ms. Neal let me walk around the room and teach the math to the other kids. It was fun — like, “hey, I know how to do this, let me show you.” She made sure I learned everything I could. Thinking back, it was less about me knowing the math and more about allowing me to be me. I wasn’t doodling or drawing or being a menace.

When I was getting ready to choose my high school, she told me I should apply to Brophy College Preparatory. She said I had the “charisma” to make it. I’d never heard of it before. When I interviewed, the dean asked me, “Why do you want to come here?” I said, “I don’t know why I want to come here. I was told it would be a good opportunity.”

My freshman year, I had culture shock. It was a lot for me to grasp. I never really adapted to Brophy, and I don’t know why. There were smart kids there, though, and I was determined to run with them. My senior year, I got into the U of A. Ms. Neal said, “I knew you would make it.”

I live close to ASU now. When people ask me, “Where’d you go to school?” I’m proud to say, “the U of A.” And it’s always the U of A. Nobody says, “I went to the ASU.”

Jonatan Noriega

Photo provided by Noriega

I was fortunate to have a full ride, but I struggled my first year. I didn’t have friends or family nearby. But once I started exploring, I found my place. I spent most of my days on campus, 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. I could sit on benches for hours and just watch people. People running and walking. I always thought, “I’ve never seen these people before and I’m never gonna see these people again.” Every relationship and interest I had revolved around the U of A: basketball and football games, Zona Zoo; my job at the Alumni Association, where I learned that being early was being on time and being on time was late. I learned to do things right the first time. Leaving Tucson after nine years of undergrad and grad school to return to Phoenix to teach was difficult for me. But it was my dream.

I still remember the stats: 30% of new teachers don’t make it past their third year and 50% of teachers don’t make it past their eighth year. I remember walking into a kindergarten class and everybody’s tiny. I got down on my knees to talk to a little kid. “Hey, what are you drawing?” This little kid, he’s all shy, and says, “cactuses.” In the back of my head I’m thinking, “actually, it’s cacti.” But, you know, I’m not going to ruin it for the kid.

And I talked to the next kid. “Hey, what are you drawing here?” And he just slams his crayons down. “We’re all drawing cactuses.”

“I’m sorry, man. I’m sorry.”

I remember looking at the professor like, “Get me out of here. I can’t be in this room. Not kindergarten.” I never stepped into a kindergarten classroom again.

I taught at Challenger Middle School during my master’s program. That place — either it makes you or breaks you. If you can survive there, you can survive teaching anywhere. It’s a

rough school. Right now, if my kids give me attitude, I’m like, “Not today. Sit down, be quiet.”

Now I’m at a high school about four miles from where I grew up. I teach freshman English and Mexican American Studies to seniors. Not all my students are Mexican, so we read stories by Latino and Latina authors from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras to give a broader spectrum of authors from their home countries. We think a lot about college in that class, working on essays, talking about scholarships, mentally preparing for the college landscape. I let them know, “You’re not going to be around a lot of people of color; that’s not a demographic you’re going to constantly run into.” And they don’t believe me. But when we go on field trips, they see for themselves.

I say, “I want you to look around.” They ask, “Where are all the Hispanic people?” I point out, “If you want to see Hispanic people here, it’s going to be you, and if it’s not you then it’s nobody.” That really clicks with them. People sometimes ask me why I don’t teach at Brophy. I say, Nah, those kids don’t need me.

I took two Mexican American Studies classes at the U of A with Professor Curtis Acosta. I was super glued to everything he talked about. I never really had role models like that growing up.

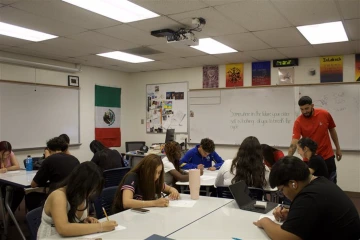

Jonatan Noriega teaching at Carl Hayden Community High School in Phoenix.

Yoselin Hermosillo

I also took Masculinity 151, which was an interesting topic. I ended up teaching a similar class for a couple of years when I was at Challenger. I had 40 boys learning what it means to be a man and how that definition changes depending on your culture. We broke apart all the preconceived notions of masculinity. The kids loved it. Once the semester was over, they wanted to take the class again.

Being a first-generation graduate gave me hope that other people in my family could do it, too. But sadly, it’s just been me. That’s why I’m so hard on these kids, but I’m starting to see the full circle. Some of those Challenger students are in college now, not just at the U of A, but all over the country. And when a freshman with college aspirations becomes a senior, I remind them, “You were interested in going to college, so come to my class — you’ll learn something.” I help them finish their applications and turn them in to the counselor. It makes me happy.

College is important because it allows you access to your dreams. A lot of kids I have want to work in the medical field, be social workers, become architects or engineers. You’ve got to go to college for those careers. Some kids want to go to trade school so they can get a good-paying job. Trade schools and colleges are equally important depending on a kid’s reasoning. I don’t have any students right now that say, “I want to go to college because my parents are making me,” or “because my parents say it’s important.” For my seniors, it’s

intrinsic. It is “I want to go to college because I want to.” I think going to college is only important if you want to go. If you don’t want to go, there are other avenues.

I used to work on class notes for the Arizona Alumni Magazine, and I remember we got this email from an alum saying they no longer wanted to receive the magazine because they graduated in the 1970s and the U of A no longer felt special to them. I was with my co-worker, Kasey — we were both seniors at the time — and I was like, “oh my God, that’s so sad.” She was shocked by it, too. I thought, “Yeah, that’s bound to happen. We’re gonna be like that one day, too.” But even now, every time I get the magazine, I get excited to read about all the stuff happening, the new buildings and accomplishments. I got so much out of the U of A that it will always be special to me. Because I know that right now, somewhere on that campus, there’s somebody like me who is a first-generation kid, and the U of A is taking a chance on them, giving them a full ride. It’s like: Here, we’ll see what you’re capable of. And that kid is doing all right. And then whenever they graduate, I know the U of A already has their eyes on the next person. And it just ripples.