'A Life in Pictures'

A CCP exhibit showcases the masterworks of W. Eugene Smith.

W. Eugene Smith, “Frontline Soldier with Canteen,” 1944, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: W. Eugene Smith Archive, © The Heirs of W. Eugene Smith

Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: W. Eugene Smith Archive. © The Heirs of W. Eugene Smith

Photographer W. Eugene Smith was only 25 when he was sent by Life Magazine to document the war raging between U.S. forces and Japan in the South Pacific. Arriving in 1943, he saw — and photographed — casualties so horrific that the government often censored their publication. Later, he remembered “a heart-rending set of pictures of some women and children caught between two fighting armies. I had just tried to save the life of a child (without luck).”

In despair, he wrote, “I have little hope that man has the intelligence to stop war.”

Two years in, he was badly wounded by shrapnel and brought back to the United States. Smith would not pick up his camera for a year. When he finally did begin to work again, no doubt thinking of the child that died in his arms, he chose to make a picture of his own two children walking hand in hand in a sunlit forest, titled “The Walk to Paradise Garden.”

Though known as a difficult man, he often saw his work as an effort to make the world a better place. Luckily for Tucson, 2,700 of his prints are in the archive at the University of Arizona’s Center for Creative Photography. Forty-five of these masterworks are now in a show, “W. Eugene Smith: A Life in Pictures,” that will run until March 2024. Rebecca Senf ’94, lead curator, has chosen photos from five of his series around themes that connect the past with the present. As she says, it is “a group of distinct but relevant subjects — war, Black women’s reproductive health, jazz, labor and industrial pollution.”

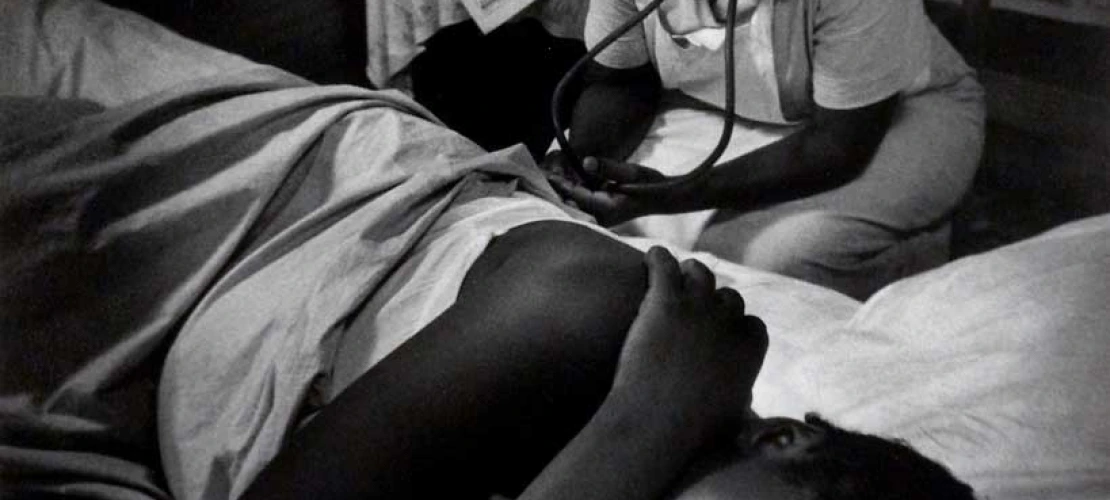

The “Nurse Midwife” photo-essay, published in Life in December 1951, follows Maude Callen, a Black nurse midwife who worked day and night for desperately poor women in South Carolina. Smith’s photos show Callen walking in the mud to see her patients. In one, she treats a Black woman behind a curtain in a makeshift clinic. In another, she is vaccinating a white baby. In those days of segregation, she served everybody in her community. Said Smith, “I wanted to make a very strong point about racism, by simply showing a remarkable woman doing a remarkable job in an impossible situation.” Readers were so moved that many sent donations that enabled Callen to open a proper clinic.

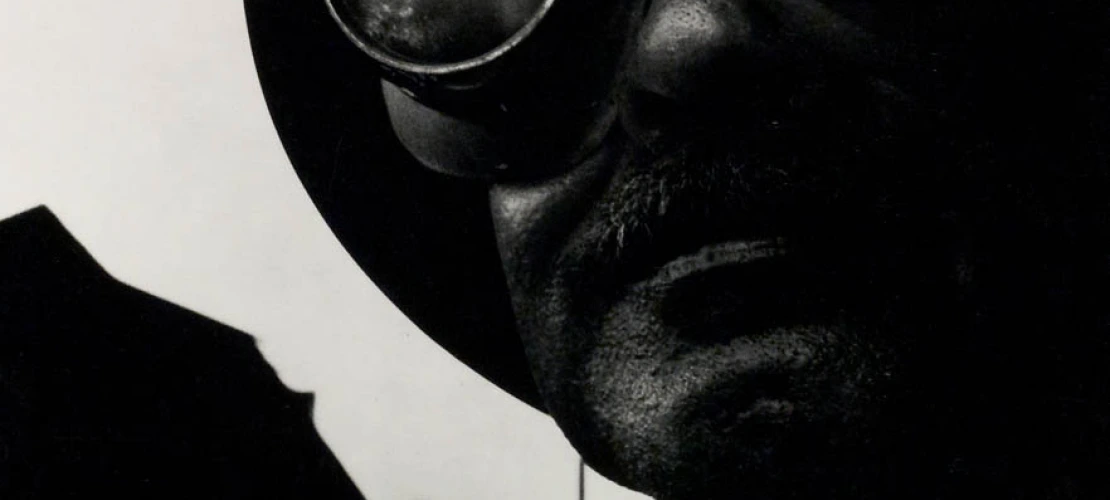

In 1957, Smith’s career took a turn when he abandoned his wife, Carmen Martinez, and their children and moved to a loft in Manhattan. Over the next eight years, he explored another dimension of the Black experience in America: jazz. Late at night, musicians like Thelonious Monk and Charles Mingus would gather in his loft and play for hours. Smith recorded an extraordinary 4,000 hours on reel-to-reel tape and took some 40,000 photographs. Curators at the CCP made a playlist from this priceless legacy to play continuously for their visitors.

Another side of Smith’s career was in postwar Japan. In 1963, the Hitachi corporation paid him to spend a year photographing their factories. Though hired by the corporation, Smith’s eye was on the hardships of the workers. In one picture, a weary group is eating lunch in a room above massive machines on the factory floor.

Smith returned to Japan in 1970 with Aileen Sprague, a native speaker of Japanese whom he would later marry. Together, their mission for three years was to document mercury poisoning in a fishery in the town of Minamata. The Chisso Corporation had spewed chemicals into the water, causing birth defects and neurological disorders among people who ate the fish. The project produced one of his most famous pictures, an image of a mother and her disfigured daughter titled “Tomoko and Mother in the Bath.” The series was published in Life as “Death Flows from a Pipe” and then made into a book, with Sprague as co-author. The photographs sparked international outrage and became an early call for environmental activism.

Smith and Sprague eventually parted ways, and he moved back to New York City in 1974. But he was in poor health, made worse by alcohol and amphetamine abuse. In 1975 — when the CCP had just been founded by John Schaefer and Ansel Adams — John Morris, a journalist friend of Smith’s, persuaded Schaefer and Adams to invite Smith to bring his archive to Tucson. They also offered a teaching appointment. Smith agreed, arriving in Tucson in 1977 with an extraordinary 44,000 pounds of freight: photographs, cameras and a lifetime of personal papers.

But his time in Tucson was short. After a disabling stroke in December 1977, a second stroke in October of the following year killed him at the age of 59. His life’s work still inspires.