The Altarpiece

The University of Arizona Museum of Art ships a prized piece of Renaissance art out for restoration.

Schoolchildren explore the Altarpiece from Ciudad Rodrigo.

UAMA

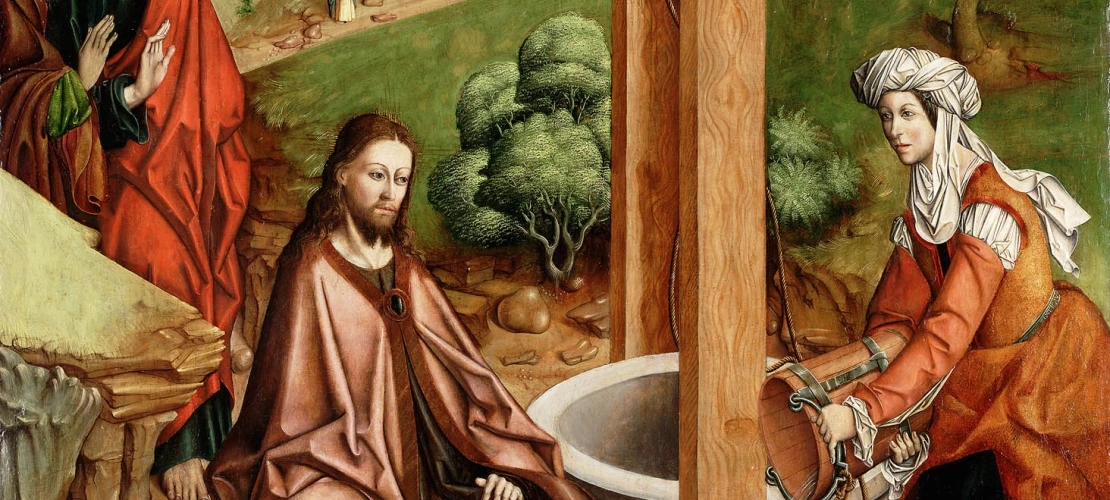

The Altarpiece from Ciudad Rodrigo has weathered the passing of more than 530 years of war, natural disasters and journeys across the sea. This year, the 26 paintings that compose the altarpiece, or retablo, will begin a new journey: a major restoration estimated to take a decade to complete.

This monumental work of 15th-century Roman Catholic art from Ciudad Rodrigo, in the Salamanca province of Spain, has been on display at the University of Arizona Museum of Art since it was donated by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation in the 1960s.

“Normally, altarpieces as large as this would have been split up and separated and sold to individuals,” says UAMA Director Olivia Miller ’05. “You have pieces of altarpieces scattered all across the world sometimes. But all 26 works [from this altarpiece] that did survive are all here in this museum.”

Miller says that to understand the present-day condition of the panels, one must first understand their history. Most were painted between 1480 and 1488, with at least three painted after 1493, by master artists Fernando Gallego and Maestro Bartolomé and their workshops. The works hung in the apse of the Cathedral of Santa María — rising as much as three stories above the altar — for decades. When the apse was remodeled, they were taken down and stored in the cloisters, never to be rehung in the church.

“By this time, it’s the 17th century. So there’s no air-conditioning, there’s no humidity controls,” says Miller. “So, they are in a room in the cloisters, subject to all kinds of weather and temperature fluctuations and humidity.”

Then, in the 18th century, the region experienced two large earthquakes. “We know that the cathedral sustained damage,” says Miller. “So we can assume that vibrations, if they were strong enough to disturb the cathedral, would have been strong enough to disrupt these paintings.”

However, most of the paintings survived those natural disasters, as well as the Napoleonic Wars at the beginning of the 19th century. The cathedral was used as a lookout tower in a battle between Napoleon and the Duke of Wellington, and the church was heavily bombed.

Most — but not all. Miller says that while we have 26 panels today, we know there would have originally been more because key scenes, such as Christ’s nativity, are missing. It is estimated that at least five panels are missing from the collection, some of which were likely destroyed during the Napoleonic Wars.

“They’ve been through a lot; they sustained a lot of damage,” says Miller. The planned conservation aims to restore them as much as possible, while also undoing some previous conservation treatments.

Miller says this is common as the field of conservation continues to advance. “As more technology becomes available to work with, we tend to discover that there were previous treatments that no longer hold up the way we thought they would,” Miller says.

For instance, one major part of the conservation project will be removing the paintings from their cradles — lattice-like structures attached to their backs once thought to help keep the work stable and on plane. Over the decades, this method has been found to do more damage than good.

Fernando Gallego, Francisco Gallego, and workshop, “The Last Judgment.” 1480-88, oil on panel. Gift of Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

The paintings will be shipped off in pairs for conservation treatment by experts at New York University as well as by private conservators, a process which will likely take 10 years to complete.

“It’s really rare for an altarpiece of this caliber and of this size to survive in the condition and completeness that it does, and so it’s certainly worth all of the effort to make sure that we carry them into the future,” Miller says.

“These paintings have been through so much in their history. We see this as the next chapter.”