Born in Front of Beans and Rice

Melani Martinez’s memoir The Molino is a revelatory look at food, family and Tucson history.

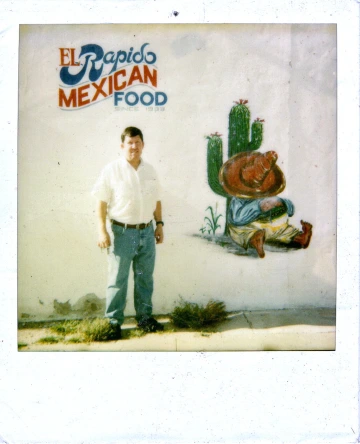

The window of the former El Rapido, summer 2025.

Chris Richards

In the fall of 2000, author Melani Martinez ’00 took a class with University of Arizona creative writing professor Alison Deming. Deming, now a professor emerita, encouraged the students to write about experiences they had every day. At the time, Martinez was working at a small restaurant in the Presidio district of downtown Tucson called El Rapido, which her family had run since the 1930s.

Martinez had worked at El Rapido since childhood. Her brother, Ricky, worked there, as did her Uncle Alberto, her father, Tony, and her grandmother and all seven of her grandmother’s siblings. (Martinez, who as of this fall is an associate professor of practice in the U of A’s Foundations Writing Program, later wrote, “I begin working for my father as soon as I can walk, talk, and take orders.” And: “I feel as though I am born in front of beans and rice.”)

A few days before the end of the semester, Martinez learned that El Rapido was going to close. On the last day of class, Deming asked students to celebrate by reading some of their work; Martinez broke down in tears. “I had no idea that it would ever leave my family, that it would ever be gone,” she says. “Suddenly, when I had to read aloud, [I got] a completely different perspective.”

That essay became the seed of a memoir called “The Molino,” published by the University of Arizona Press in September 2024. (It has since been named a Southwest Books of the Year Top Pick by the Pima County Public Library and been shortlisted for the Nach Waxman Prize for Food and Beverage Scholarship by Kitchen Arts & Letters, a New York City bookstore specializing in writing about food and drink.)

“The Molino” is not a linear memoir. Instead, it unfolds as a series of vignettes held together by brief interludes attributed to a character called el pensamiento, or “the thinker.” The vignettes are, for the most part, small: anecdotes, images, the kind of experiences that seem peripheral to our lives but over time come to illuminate and even define them.

Martinez remembers her father not quite being sure what to make of it. She tried to explain that she was only writing the story the way she’d learned it: in fragments, over time, not always in order. “You would give me one little piece of the puzzle,” she remembers telling him. “And then, you know, literally seven years would go by, and you’d give me another.”

The idea for el pensamiento came from a caricature of a sleepy Mexican man in a wide sombrero slumped against a Saguaro cactus that Martinez’s uncle, Alberto, had painted on the side of El Rapido in the late 1980s. Martinez remembers being confused as to why people were so offended by it.

Later, she realized it was a kind of curse in search of redemption. “It felt really good for me to be able to redeem that image,” she says. “To turn it into something that had authority, that had spirit, that had almost — you know — no beginning, no end.” He also became a way for Martinez to reconcile herself to aspects of her family that she had turned away from when she was younger. “He speaks in scripture,” she says. “I had this other part of the story of not being able to retain the faith that my grandparents and great-grandparents had, and then, you know, rediscovering it.”

The story of El Rapido doubles as a story about the changing nature of downtown Tucson. Historically, the Presidio had been a community of Mexican Americans and other people of color; by the time Martinez was working at El Rapido, it was oriented toward tourists and law offices. “[Gentrification] is something we continuously talk about in this city,” she says. “There’s this sense of wanting to improve things but to not make it inhospitable for people who were here before.” (Martinez cites U of A professor emeritus Lydia Otero, in particular their book “La Calle,” as a major inspiration for how to have these difficult conversations in a productive, honest way.)

“The Molino” is out in the world and doing well. In the meantime, Martinez is focused on her work at the university, in particular a first-year writing class about the Sonora Borderlands housed within a grant project called Project ADELANTE and designed, in part, to give the university’s Hispanic population a novel way into the gen-ed English curriculum while supporting student retention, too.

“I’ve been trying to get students to be more open about the kinds of experiences they’ve had in Tucson,” she says. “To write that in class so that they feel like they belong.” This becomes as much a part of the work as the work itself. “I have been, I feel like, a conduit for helping other people,” she says. “Our fantastic students.” She was one once, too.

More Related to This Story

Meet Melani Martinez

Explore Melanie's work as a creative nonfiction writer, poet, and educator. Read more of her stories on her official site.

"The Molino" On KJZZ

In this KJZZ interview, Melani Martinez shares the roots of her family’s restaurant and how it shaped her hybrid memoir.

Purchase a Copy of "The Molino"

Set in one of Tucson’s first tamal and tortilla factories, The Molino is a hybrid memoir that reckons with one family’s loss of home, food, and faith.