More Than Just a Pretty Place

How the Campus Arboretum is using plant science to help us face our climatological future (and look good doing it).

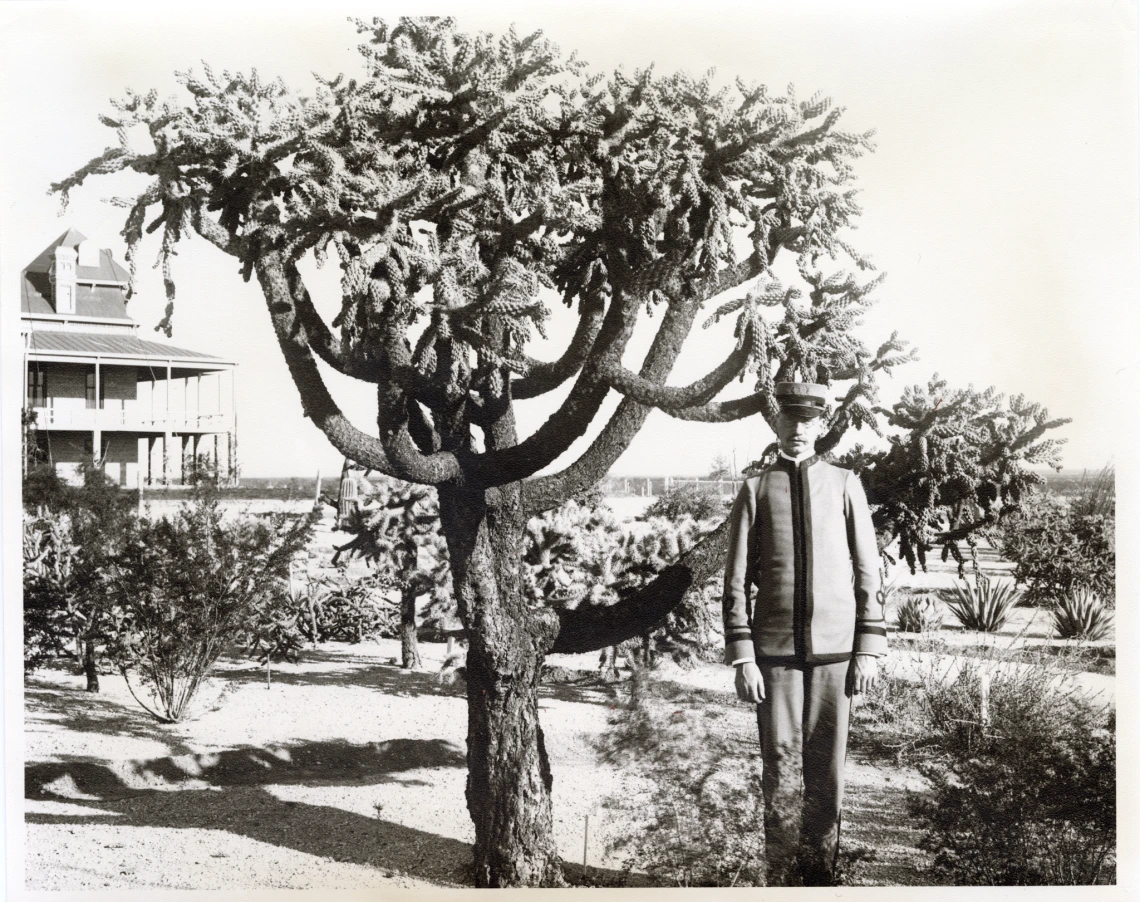

A young cadet in the Old Main cactus garden, circa 1890s.

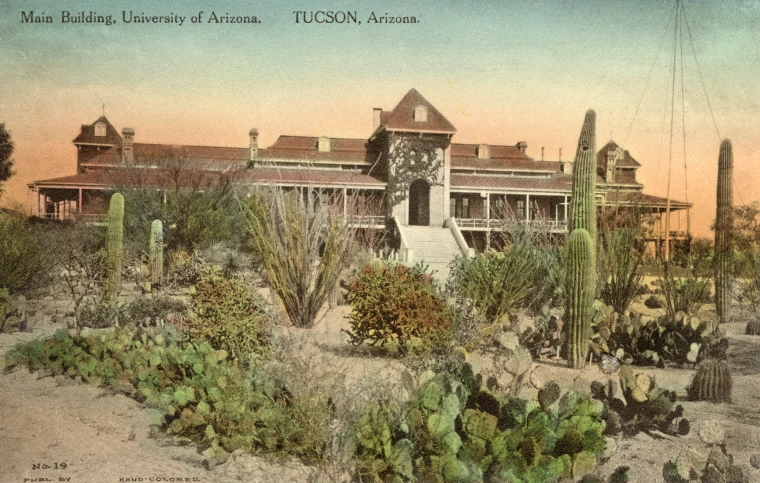

All images courtesy Special Collections, the University of Arizona

Stand anywhere on the University of Arizona campus and look around:

What do you see?

Buildings, sky, trees. Some of those trees, like the white floss silk tree on the south side of the Engineering Building, are distinguished and eccentric. Others, like the young sycamores in the Student Success District behind Bear Down Gym, fade into the scenery. All of them are part of a history of discovery and experimentation dating back to before Arizona’s statehood we now call the Campus Arboretum.

The arboretum is not a specific place. It is not a garden or a greenhouse or a museum. You cannot take the arboretum in like a play or cover it in an afternoon. Instead, the arboretum is everything on campus that grows, from the humble bushes and understory plants that line the shady sides of buildings to the trees at the edges of parking lots to the carefully curated coral garden on the Mall outside the Student Union Memorial Center. It is a collection, a conversation with the land, the climate, the past and — most importantly — the future.

“I like to tell this story about one of the U of A’s early faculty members, Robert Forbes,” says arboretum Director Tanya Quist. “He would travel around the world selecting plants and trees he believed would be good agricultural commodities for Arizona, knowing agriculture could give us an economic basis to become a state.”

One of those crops was the olive tree. Could they survive here? Could they thrive? And which varieties, and from where? Spain? France? Italy?

Forbes had seen the way they laid out gardens in Europe, the neat rows of identical-looking trees. But he wasn’t just planting a garden, he was running an experiment. “He wanted to assess which of these different types of olives would perform best here,” Quist says. Typically, this would be done by arranging plants in a split-plot or randomized design: a square, or a rectangle.

Forbes had a thought: What if we plant an allée of olive trees, something neat and pretty that people can walk through and admire, but alternate varieties in such a way that we’re still running an experiment? “It was a brilliant way of recognizing that a university is a formal, elegant place,” Quist says. “But he was also carrying out science.” Forbes planted that allée in the 1890s, just inside Main Gate. We call it Olive Walk.

Walk east and you can almost see the history of campus unfold in stages, from Olive Walk to the cluster of cacti around Old Main to the palm-lined lawn we call the Mall, which replaced a cactus garden in the 1950s; from the native, drought-tolerant plantings of the ’80s and ’90s through the swales and drainage basins you see around new projects like the Grand Challenges Research Building today — modern adaptations designed to capture and reroute rainwater as we enter a hotter, drier future.

The history of the arboretum is a history of adaptation and change. “When I started out as a student, all the plant material for Tucson was coming from California,” says Mark Novak ’80. Novak completed his landscape architecture degree at the U of A when the program was still housed in the agriculture school and later served as the landscape architect on campus for 30 years. He saw the formal establishment of the Campus Arboretum in 2002. He saw the cultural winds shift toward conservation and sustainability. He saw campus transition from what it had been to what it is today.

Take mesquite and palo verde trees: In the ’70s and ’80s, they were shunned, Novak says. “In Texas, they were considered weeds.” But they worked well in the Tucson landscape and were promoted by faculty like Warren Jones and Charles Sacamano as drought-tolerant alternatives to some of the more common ornamental plantings of the time — a smart choice from a conservation standpoint, but also one that shifted the market for plantlife in the region.

“You’d have folks like Ron Gass, who was in charge of Mountain States Wholesale Nursery — you know, the largest commercial nursery in Phoenix — utilizing that [research],” Novak says, a partnership between campus and community that helped integrate scientific research with commercial production. In time, the experimental became the common. Now you can see mesquites and palo verdes in just about every urban neighborhood in the Sonoran Desert, not just because they look nice, but because this is where they belong.

A hand-colored image of the cactus garden formerly outside Old Main, pre-1950.

The push for native plantings was crucial, but in order to sustain ourselves we’ll need to continue to evolve. A few years ago, Quist went to a conference in Albuquerque where the city had laid out a succession plan for their trees based on current climate predications: What was surviving now, what might perform well in the future. “It looks like Tucson,” she says. “So I thought, ‘Well, when our climate gets hotter — and it’s actually getting disproportionately hotter [compared to Albuquerque] — where do we go? Who do we look to as a model?”

Part of what made Robert Forbes and some of the U of A’s other early researchers’ work brilliant was the insight that you could predict what might happen in the Sonoran Desert by comparing it to places with similar climates. What could we learn from North Africa? What could we learn from the Middle East? “This was decades before the field of ecology was even a thing,” Quist says.

Certainly it’d be nice to travel the world collecting plants, but this is the 21st century. Over the past year and a half, Quist and other arboretum researchers have combed through databases aggregating the holdings of public gardens, formal tree inventories and citizen scientists from all over the world, including how those trees are faring where they are. They then correlate those observations with data to predict what might make a good climatological match here in Tucson — a project that could light the way not only for campus but for all of Arizona. “It’s not just campus as a bubble of science-based practices,” Quist says. “We’re a land-grant institution. This is an opportunity to educate by providing a responsible model of greenspaces in full view of the community.”

This is not a solitary effort. If the arboretum makes recommendations on which species might work best here, it’s the landscape architects who develop design and specification standards for those plantings and facilities managers who draw up the budgets, plans and schedules to ensure day-to-day care.

“We called it a three-legged stool,” Novak says, remembering the arboretum’s inception under founding Director Libby Davidson: the arboretum, the landscape architects and facilities management. “We were all working in the campus landscape in different capacities and thought it made sense to work together.”

The job can be as grand and romantic as the maintenance of the Heritage Trees, which constitute some of the oldest and most unique specimens on campus. But it can also be as ordinary as figuring out how to plot green space around underground utility lines being laid in the Campus Historic District, a project Quist likens to setting a work of art in a busy intersection instead of a climate-controlled museum.

On an informal bike tour with current landscape architect Chris Stebe ’97, we stop at a parking lot. You know the one: big, flat, gray, gravel. Nothing special about it, except maybe the massive mesquite at one end. “We’ve got them all over the place,” Stebe says, the mesquites. Still, they frame our experience, work on us, embody our idea of campus as fully as their pedigreed peers. This is the crucial and invisible work the arboretum does. So if you’ve ever taken an extra spin around the lot looking for a shady place to park, welcome: You’re sitting on the three-legged stool.

Campus is a place, but it’s also a collection of moments, a staging area for our lives: the perfect sunset (how do we have so many?), a picnic on a bench. People fall in love here, people get married — I myself officiated the wedding of two friends outside the Douglass Building back in 2017. (Thank you, Bill. Thank you, Dana.) People memorialize their friends and family on bricks and plaques and no doubt perform countless other private rituals to maintain connection with an ever-receding past. My kids learned to ride their bikes on the Mall. Then they grew. Other kids are riding those bikes now. That’s part of campus, too.

“When you talk to people at alumni events or about their experience on campus, it’s hardly ever about a building,” Stebe says. It’s the space, the big picture, “the feelings and emotions that are tied up [there].”

Of course, that big picture might change. Look at pictures of Old Main from the early 1900s and you won’t see the Mall; look at pictures of the Mall from the 1960s and you won’t see the desert landscaping that followed. We don’t plant Aleppo pines the way we used to, because they aren’t surviving. A student who graduated in 2024 will remember a different campus than one who graduated 40 years earlier. There is a thought experiment here: If we were to replace every single thing here with something else, would we still call it “campus”?

One answer is: of course. We talk as an institution about the value of research, of progress, of adaptation and innovation. “One of the biggest changes I’ve seen over the past 30 years is an increased student interest and involvement in sustainability,” says Novak. “Incoming students are asking: ‘What are you doing in this area? What are you doing to help create a sustainable future for us?’” What better way to express our land-grant commitment than to renew our commitment to the land?

It feels good, the arboretum: all these trees, all this nature. But feeling good isn’t the point. “I want people to really begin to think about trees as infrastructure,” Quist says. “I want them to think about trees as living things, contributing in the same ways that streets and utilities do.”

She understands the charge people get from weird and beautiful trees as a gateway for a deeper experience. “Weird and beautiful things are my jam,” she says. “But I think what really is more compelling to me is trees that are tough. Trees that are in it with us.” The workhorses, the daily drivers, the team players — living beings whose mere existence verges on self-sacrifice. “I think about these street trees that are literally taking the brunt of it,” Quist says. “They’re out in the median in the middle of a roadway. They probably don’t have enough water. They’re getting all that reflected heat from the asphalt and pollution from the cars. And they’re absorbing all that in their leaves so that we don’t breathe it in.”

It’s a job. And the job isn’t getting any easier. Campus may look a little different than it used to, but the mission of the arboretum and the people in its orbit is the same: to leverage science to bring us into alignment with the world around us. What will perform best here now? What will stand the best chance of surviving when we’re gone? The sycamores in the Student Success District might not look like much today, but Stebe estimates they could get to be 60, 80 feet. Give them care.

Interested in Learning More?

Tree Climate Surveys

Discover opportunities for community members to contribute to the Campus Arboretum’s research.