Embracing Creativity

A shared vision for integrating the arts campuswide

Andrew \"Andy\" Schulz

Andrew “Andy” Schulz, the University of Arizona’s first vice president for the arts, is an art historian who can tell you everything you ever wanted to know about the 18th-century Spanish artist Francisco Goya.

His book “Goya’s Caprichos” celebrates a series of riveting black-and-white etchings and aquatints by the renowned artist. Filled with images of rogues and monsters, saints and sinners, the caprichos (“whims” or “caprices”) catalog nothing less than the vices and virtues of all humanity.

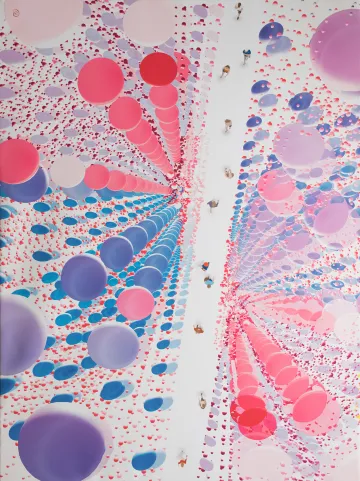

Image: Xinyu Zhang, “Wander Around #10B,” mixed media: acrylic and digital on canvas, 40 inches by 30 inches, 2018

Connecting art and innovation to the research enterprise

“Art moves us and helps us understand what it is to be human,” says Schulz. “There’s always a place for that intrinsic value of art, for the power of hearing a beautiful piece of music or seeing a beautiful work of art.”

Working out of an office in the Fred Fox School of Music, he can hear music floating out of student practice studios all day long. Or he can take a peek at student painters making new masterpieces at their easels in the nearby School of Art or listen to young thespians rehearsing plays in the School of Theatre, Film and Television. Farther afield, he can watch dancers at the School of Dance.

As arts VP — as well as dean of the College of Fine Arts — Schulz is not in the classroom teaching the glories of art, as he did earlier in his career. He’s on a different mission, charged with bringing art into every nook and cranny of the university and integrating the arts into all areas of academic life.

“When I first interviewed with President Robbins, it was clear that he shared a vision that I have for the arts in higher education,” says Schulz, who was lured away last year from Penn State, where he was associate dean for the arts and architecture. He and the president, he says, agree that the arts are “a core mission of the university.”

Their grand vision imagines a re-do of the university’s arts venues and even the construction of new buildings devoted to the arts.

Schulz already is working with an architectural firm on preliminary ideas for a much-improved Arts District on the northwest corner of campus, where museums and performance venues intersect with arts studios. The team is working on a master plan that would unify the district with the new Honors Village north of Speedway Boulevard and stretch to Second Street on the south.

“The Arts District would be a gateway into campus,” he says.

The UA Museum of Art — which recently made headlines nationwide for its recovery of a stolen Willem de Kooning painting that had been missing for 31 years — would get a long-hoped-for new home under the plan. The old museum is cramped and hard to find; the goal is to construct a new building with a more welcoming face to the community and more space for the collections. The old building would be preserved and turned into studios and classrooms in the School of Art.

A brand-new, state-of-the-art performing center in the district would have 1,200 seats, making it more suitable for some shows than historic Centennial Hall — twice the size at 2,500 seats. The venerable Centennial, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, would get some updates and a clear pathway would link it to the Arts District, for example.

One change at Centennial is past the planning stage: A newly hired executive director, Chad Herzog, hailing from the International Festival of Arts and Ideas in New Haven, will take charge of the theater’s UA Presents program in August.

“He’s going to be great,” Schulz says.

In addition to creating an improved Arts District, Schulz plans to revitalize the university’s dormant public art program, planting new pieces across the campus. Karlito Miller Espinosa will create a mural on the Speedway-facing walls of the Joseph Gross Gallery this coming fall, with the help of a few undergraduate students he’s taught. MFA student Dorsey Kaufmann used funds she earned from the Marcia Grand Centennial Sculpture Prize to create the current installation in the underpass this past spring.

Schultz’s plans for the curriculum are equally ambitious.

“For a long time, the arts have sat at the margin of major public universities,” he says. “We have great professional training programs in the arts” — in the schools of visual art, dance, music, and theater, film and television — “but the reality is that only about 3% of students are in those programs. But experiences in the arts aren’t just for art majors: They’re for all students.”

Even the university’s renowned programs in the sciences and engineering can benefit from embracing the arts, Schulz says. “What happens when you start integrating the arts into that research enterprise? You start changing the kinds of questions people ask when you have creative people on teams of researchers.”

And, on the practical side, scientists might benefit from learning the art of storytelling to explain their research. Film students could work with scientists on documentaries, and theater students could pose as troubled patients to help medical students learn effective bedside manner.

Some initiatives are already in place. The UA Museum of Art staged a critically acclaimed exhibition early this year that paired six scientists with six artists; the multidisciplinary teams used paintings, photographs and videos to bring environmental issues to light.

At the Center for Creative Photography, Meg Jackson Fox, a new curator for academic and public programs, is tasked with brainstorming ways non-arts classes can benefit from the CCP’s vast holdings. An astronomy professor, for example, might bring a class to see the museum’s collection of space photos, and an English professor could assign students to write about the current exhibition on poetry.

No ideas are off limits for Schulz. He’s already working with Ron Wilson, the university’s new Title IX officer, on ways to use the arts to communicate ideas about gender equity and student conduct.

“What would be the effect of having a student theater troupe that can create and perform pieces on a whole range of issues?

“We do have grand ambitions,” he adds with a laugh. “But if you’re not going to aim high, why bother?”