'Alumnus' to 'Alumni'

For 100 years, the alumni magazine has captured university history in memories and moments that reflect the times.

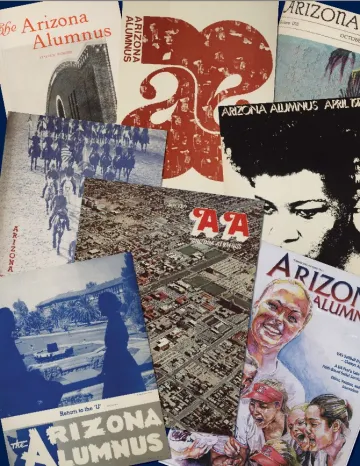

Previous issues of the magazine gave voice to Black campus leaders and celebrated the UArizona softball team, among others.

/ Image courtesy of University of Arizona Libraries, Special Collections

“Many alumni,” wrote the editors of the University of Arizona’s inaugural alumni magazine issue, “will not receive this publication because their address is lacking in the office of the Alumni Secretary. In an effort to locate these alumni we are publishing a list, asking the help of all in locating them.”

The date of publication was Nov. 15, 1923. The magazine’s name was, and would long remain, Arizona Alumnus. The list of alumni with unknown addresses included 186 names, short enough to fit on a single page of the magazine — which was printed on paper sized closer to a paperback novel than the glossy periodicals we know today.

This was the beginning: UArizona had not yet turned 30 years old, and the earliest “lost” graduate, Edward M. Boggs, bore a class year of ’97, as in 1897. The globe spun in the short breath between the Great War and the devastation of a second submerging conflict.

Only a few years before, the Spanish Flu had spread unabated, claiming the lives of 50 million people around the world.

The first editors of Arizona Alumnus — Harold Wilson ’22, C. Zaner Lesher ’17 and A.L. Slonaker ’21 — intended their publication of 11 pages to unify and inform, but they must also have meant to entertain.

A two-page spread encouraged readers to watch the Wildcat football team, whose players did not then wear helmets, “wallop” Santa Clara on Thanksgiving Day. A half-page section titled “On the Campus” declared Yuma’s Marion Doan the “brainiest” student in the first-year class, reporting that “in the Alpha army test,” administered to the whole year by Dean Frank Pascal, “she scored 189 points out of a possible 212.”

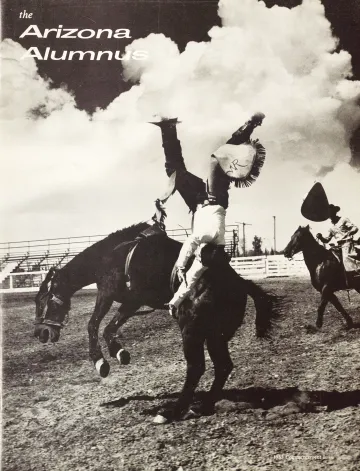

The University of Arizona’s alumni magazine dates to 1922 and over the years has reflected an ever-changing campus community.

/ Image courtesy of University of Arizona Libraries, Special Collections

Arizona Alumni Magazine turns 100 this year, though publication stuttered from 1937 to 1940 as the United States braced for and then entered World War II. And to hop, skip and jump through a century of issues is to watch the publication chase the intentions of Wilson, Lesher and Slonaker — and to see how the publication reflects not only the university but also the nation and world within which the university exists.

The magazine has morphed again and again since November 1923. Then, the saddle-stitched booklet featured a photograph of Old Main on the cover, the image presented in a washed-out blue, the rest of the issue in black and white. Ten years later, the magazine’s subscriber base had jumped from less than a thousand to 3,700 — a number that would only continue to rise, touching 6,000 before 1937 and 100,000 by 1986. In 2022, when the university enrolled its largest and most diverse class ever, the magazine was sent to 260,000 alumni.

In the aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks, the magazine printed on a stark, black cover a call for togetherness from then-UArizona President Peter Likins: “We are a University community. We gather people from all races and religions of the world, and we all belong here. We must hold together.”

In 1934, on the other hand, the staff had tried mostly for humor, serving up a surprise parody issue: an imitation of Time magazine that made mention of the seemingly apocryphal Wildcat football figure “John Tucson.”

“The reaction [to the issue],” wrote the editors — who included Pearle Hart, likely the first woman to serve in an editorial capacity at the magazine — “varied from scathing criticism and personal denunciation (a copy of which was sent to [then-University] President [Homer LeRoy] Shantz) to highly complimentary remarks from the editorial sanctum of Time itself.”

If the magazine reveals something of the university’s spirit and character through the simple action of chronicling its milestones, the image distilled is often in the direction of inclusivity and access, however delayed. In the protest-propelled ’60s, the publication produced a series of “student-participation issues,” with articles like Judy Sampson’s “Of Curbs, Crosswalks and Stairways” giving those then on campus the chance to use their voice.

Spring 1970, bearing the subtitle “Black Talk,” gave its opening pages to the voices of Black campus leaders such as Gale Dean, then chair of the Black Students Union. Dean spoke, in that issue, of his “disenchantment with student body government as it is today.”

Just 10 years ago, the magazine retired “alumnus,” the masculine singular term for a graduate, in rebranding itself as Arizona Alumni Magazine — “alumni” being plural.

For a stretch in the ’60s, the magazine also included a game on the inside back cover: the “J-crostic,” not quite a crossword puzzle, not quite an acrostic poem, yet borrowing elements from each.

To leaf through 100 years of Arizona Alumni Magazine is, too, to be reminded of the giants of their fields who have graced the university’s grounds, including Andrew Ellicott Douglass, whose early work in dendrochronology led to the founding of the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research in 1937; golfer Annika Sörenstam, who won the 1991 NCAA title as a first-year student-athlete before setting records on the professional tour; and Fritz Scholder, a self-defined expressionist whose work was on exhibit this summer at Phoenix’s renowned Heard Museum.

“I always knew I would succeed and do what I always wanted to do, which was simply to paint,” Scholder said in a 1986 first-person profile, also describing his first trip to Tucson, when “a race car driver friend drove [him] across the desert at 100 miles an hour.”

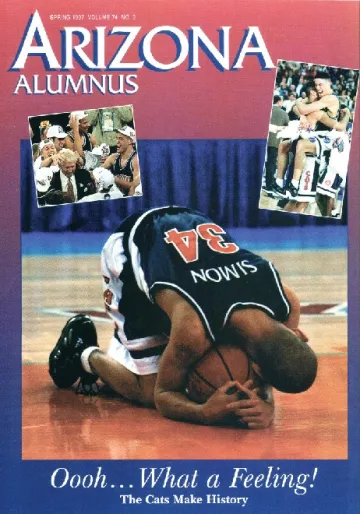

/ Image courtesy of University of Arizona Libraries, Special Collections

Then there is Lute Olson, who guided a men’s basketball team that included future NBA standouts Jason Terry and Mike Bibby to the 1997 NCAA championship, and the Wildcat softball program, winner of eight national titles between 1991 and 2007 behind coach Mike Candrea.

The magazine’s register, of course, mirrors the events it is charged with bringing to a wide readership.

In 1978, the publication extolled the achievements of the UArizona astronomy program, where researchers at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory had developed an imaging telescope aboard Pioneer 11, the first NASA space probe to reach Saturn.

Decades later, in winter 2011, the magazine published a poignant special issue devoted to the shooting of then-Rep. Gabby Giffords, featuring images of and statements from President Barack Obama, who came to Tucson in hopes of consoling the community, and Daniel Hernández, who had saved Giffords’ life.

“The editors of this publication realize that they have only made a humble beginning, but they propose to make it bigger and better with each issue,” wrote editors Wilson, Lesher and Slonaker in January 1924. It’s a statement that resounds even today.