In Search of an Answer

How a grandfather’s question sparked the curiosity that drives one doctoral candidate’s research.

Richelle Thomas, a doctoral candidate in environmental science, studies how uranium, arsenic and other heavy metals become absorbed by medicinal plants traditionally used by the Diné (Navajo) community, of which she is a member.

/ Chris Richards photo

Richelle Thomas’ grandfather was a Diné (Navajo) medicine man, and her grandmother was a traditional herbalist. From the time she was a young girl, they taught her about plants, the spiritual protocols for harvesting wild herbs for medicines, and the ceremonies and prayers that accompanied them.

Today, Thomas carries on her grandparents’ legacy of working with plants as a doctoral candidate in the University of Arizona Department of Environmental Science at the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

“My grandpa was an Indigenous rights advocate and an advocate for environmental and human rights. He was big on the protection of spiritual practice of Native people and was passionate about the preservation of the environment and sacred sites,” Thomas says.

“As a young person, I watched his work, and it was natural for me to be curious about it. I went to school for science, but it wasn’t until I was working on my master’s degree that I started really questioning a lot of things.”

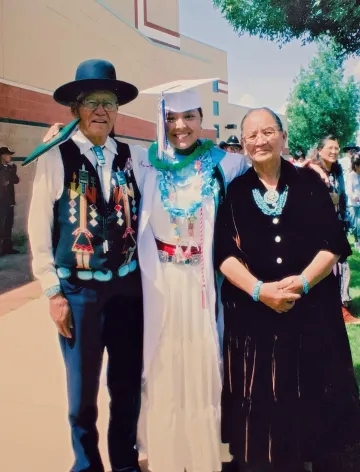

Thomas’ dissertation draws inspiration from her grandfather, a Diné medicine man, and grandmother, a traditional herbalist.

/ Provided by Richelle Thomas

Thomas says that during the second semester of her master’s degree work, her grandfather asked her a question that stuck with her and has become the central focus of her work today. While visiting him, she explained that she was studying the impacts of uranium on the environment. “Before he passed on, he asked me, ‘How do heavy metals in the environment affect humans?’ Because we use plants from areas affected by mining: We smoke them, we drink [teas made from] them, we apply them to our skin like lotions and shampoo. And I didn’t have an answer for him at the time,” she recalls.

Thomas says that a lot of medicine men and women had the same question, and she wants to discover the answer for them with cultural sensitivity toward the spiritual perspective.

“Listening to my grandfather’s question and pursuing the answer has become my career,” she says.

Thomas’ dissertation research investigates how heavy metals like uranium and arsenic are absorbed by and accumulate in the medicinal plants traditionally utilized by the Diné. Other tribal communities, she says, use the same or similar plants and are also often impacted by mining.

“My grandfather used these plants pretty much every day, seven days a week, for over 60 years,” she says. “Even at a very low dosage, we have potential for a very long chronic duration of exposure to heavy metals. I want to look at things like the pulmonary risk and the renal risk and see how heavy metals in medicinal plants might have a significant role in someone’s health.”

Her fieldwork on the Navajo Nation consists of sampling soil impacted by uranium mining areas. After screening the soil for contaminant levels, she will use the soil in greenhouse studies at UArizona to grow medicinal plants from seeds. Because these medicinal plants grow in very limited quantities, Thomas won’t collect plant samples from the Navajo Nation, as doing so would put them at higher risk of extinction in the delicate ecosystem.

“There’s so many different places on Navajo you wouldn’t think there are plants, because it just looks like desert,” she says. “But for generation after generation, the location has been passed down through oral history for where to find plants. Often these spots are less than half an acre.”

Thomas’ work also includes community engagement projects. In partnership with tribal communities and chapter officials on the Navajo Nation, Thomas plans to build a greenhouse and dedicate time to teaching STEM education focused on the history and impact of mining contaminants as well as the cultural and spiritual significance of medicinal plants. She also will partner with another community using a hoop house for educational programming.

“One concern that came up in this community is the safety of the soil that people are growing their food in. Corn, for instance, is one of our sacred plants,” she explains. “We want to do an agricultural safety assessment, screening the soil there, and get them connected to experts in this area on how to alleviate some of the risks.”

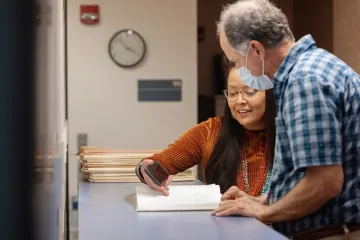

Thomas discusses the historical range of Hopi tea greenthread, a medicinal herb, with George Ferguson, senior curatorial specialist at the campus herbarium.

/ Chris Richards photo

Translating her findings and communicating her research in the Navajo language so that traditional practitioners, who are often elderly, can better understand it is a deeply important part of Thomas’ work. She is adamant about keeping the communities informed about her research and encourages dialog throughout the research process, to ensure that the community understands the results at the end of the project.

“Researchers need to be more aware of how to do research in Native communities — and how to do research with them,” Thomas emphasizes. “Traditional people, like my grandpa, they’re more experts than I am on these topics, because they have more cultural and spiritual responsibility to these places. I had to be more sensitive to that. It’s being respectful and responsible to Native people.”

Thomas also plans on advocating for other Indigenous communities around the world who have faced development that depletes their land of its natural resources in ways that negatively impact their cultural resources. “I think we need to preserve what we have left,” she says. “And I’m still thinking about how to do that. I’m looking more toward policy initiatives on Navajo as one avenue for preservation.”

Thomas’ research may show that heavy-metal accumulation in medicinal plants has a negative impact on human health, but she says that doesn’t mean the solution is to simply stop using them. “Because of the spiritual use of these plants, you can’t necessarily say,

‘You can’t use this; you can’t practice your ceremonies.’ It’s insensitive, and it could even be traumatic,” she says.

“I’ve been thinking about how we’ll solve the health risks if that comes up. And if that happens, we need to have an alternative area to harvest these plants.”

She says that if it’s necessary to find alternative locations to collect ceremonial plants due to contamination risks, new options for harvesting will come from communicating with traditional healers.

Thomas points to a photograph of her grandparents that she keeps next to her computer as a source of encouragement and inspiration for her work. And she draws from Navajo prayers as a source of resiliency and strength. “I always think about how my grandpa was able to integrate that into my education.

“Whenever I’m overwhelmed, I look at his photo and think about how he never complained. He always had time for people; it didn’t matter if it was midnight or 3 a.m., when people came to his house for medicine or ceremonies, he would open the door for them.”

She says she wants to find time for people in the same way. And answering her grandfather’s question keeps her motivated and curious.

“It doesn’t feel like work. I feel like it’s just become a part of me.”