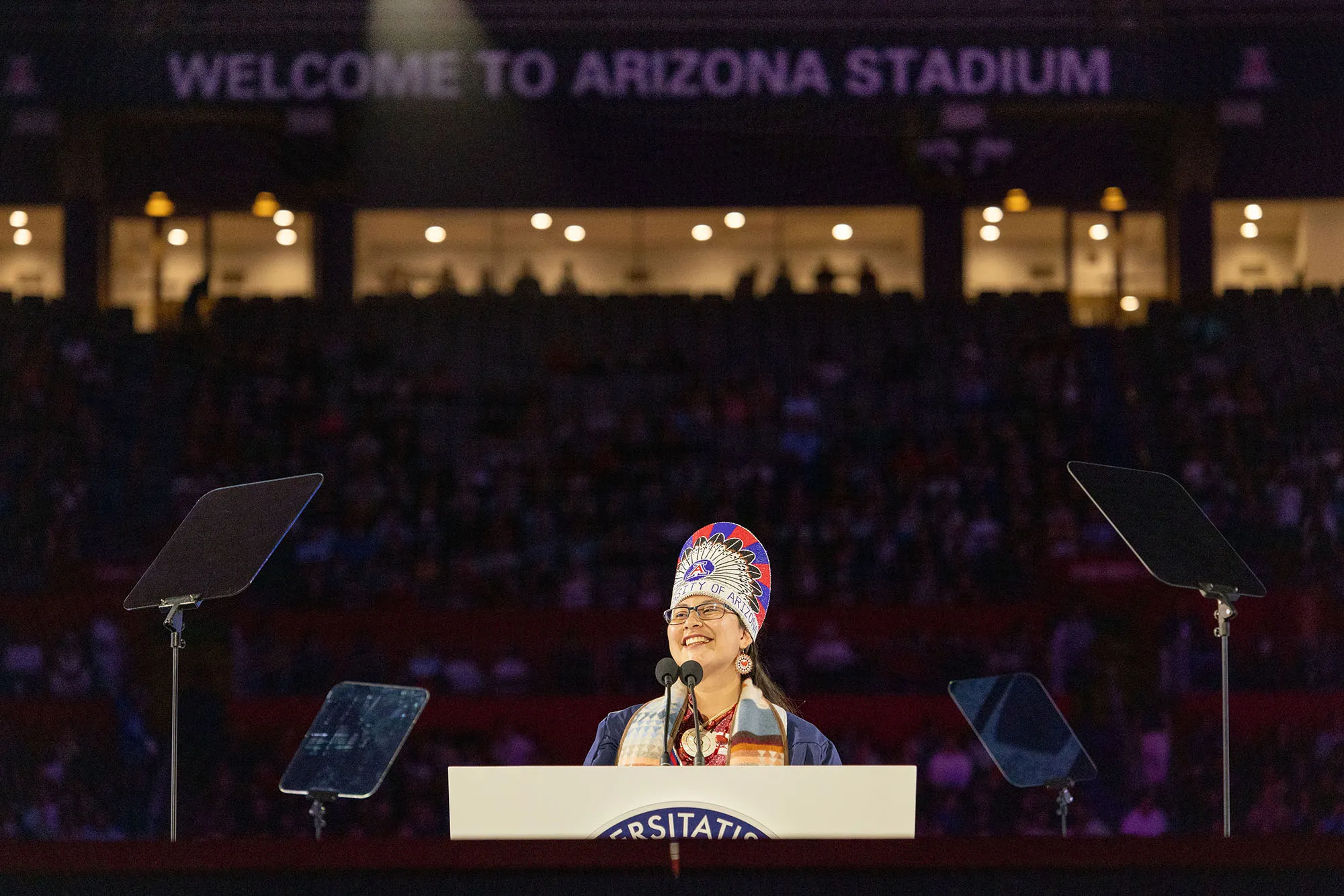

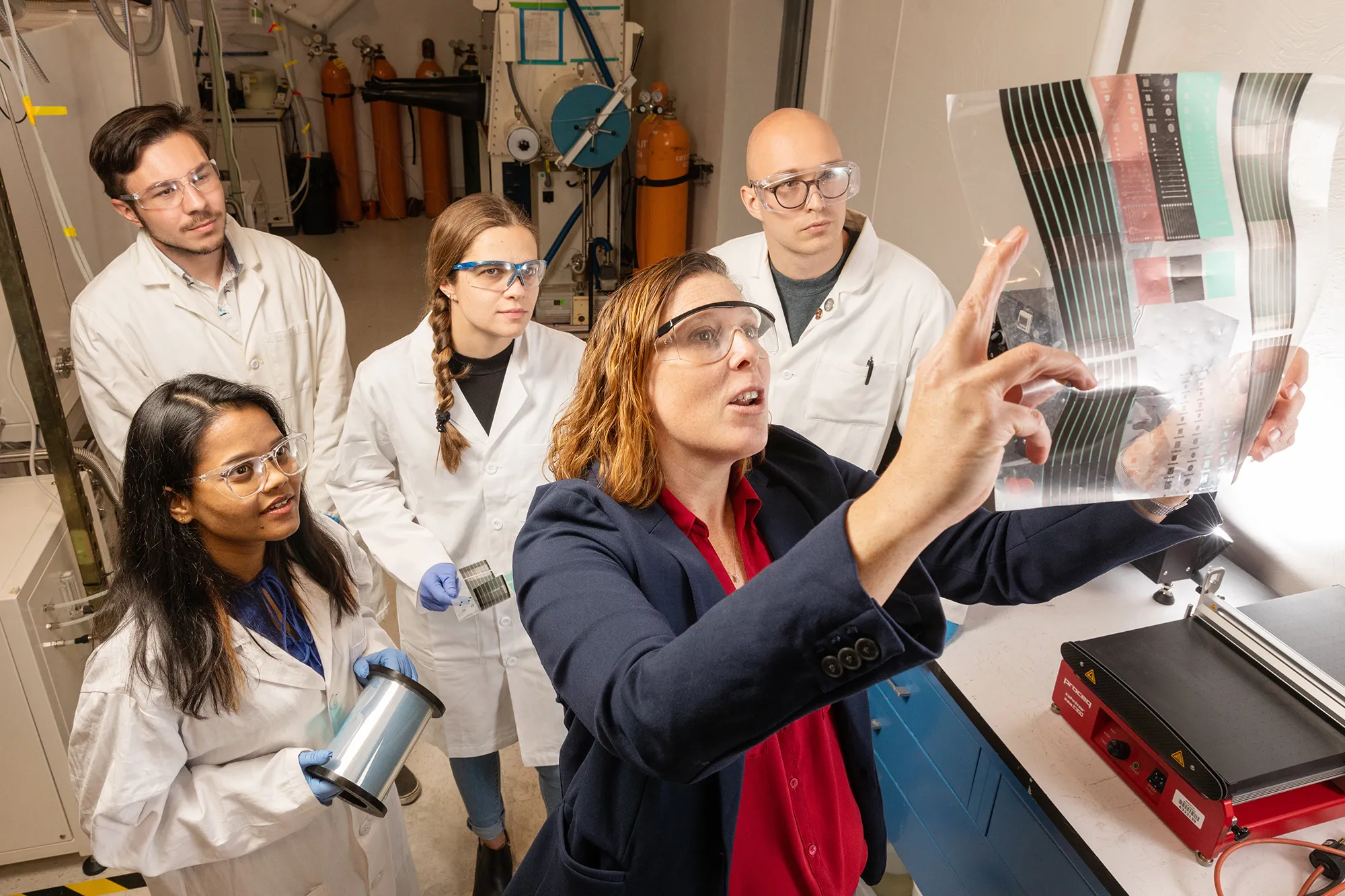

‘This hope, this profound inspiration from the young who say, “Yes, we can. Yes, we will. Yes, we are.” It is the delight of my life to be here, working at this time with these people to try and change our climate future.’

— Joellen Russell, oceanographer, climate scientist and University of Arizona Distinguished Professor of biogeochemical dynamics

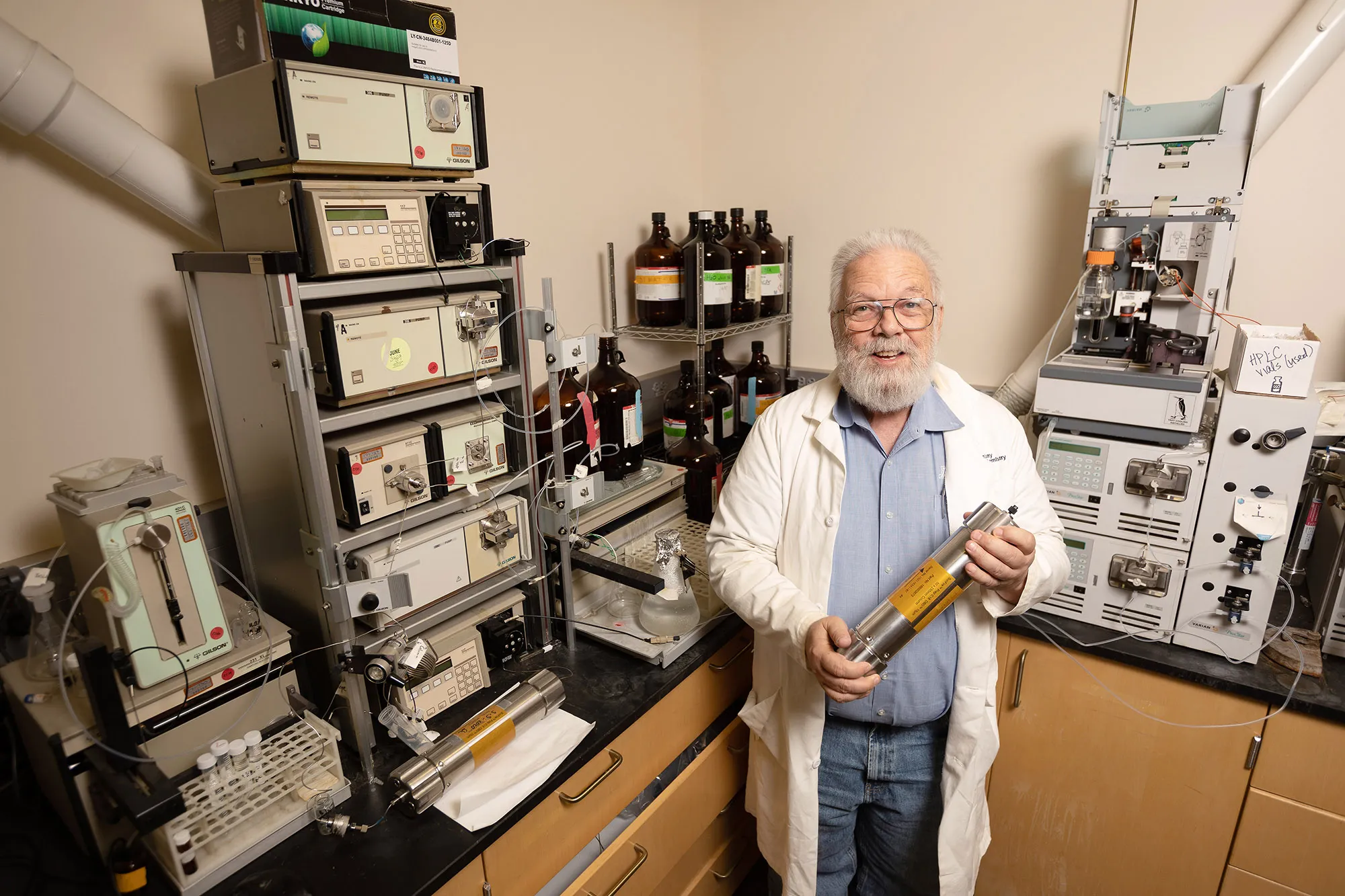

An oceanographer raised in a fishing village of 3,000 along Alaska’s Baldwin Peninsula, UArizona professor Joellen Russell knows that ‘global warming is ocean warming’ — the oceans shoulder the brunt of climate change.

/ Chris Richards photo

Joellen Russell phrases what she calls “the problem of our age” as a question: “How do we bend that carbon dioxide curve?”

Her high-tech research seeks answers in the depths. South of 30 degrees latitude, far beneath the surface of the Southern Ocean, she and her colleagues at institutions across the country submerge tubular yellow robotic floats for observation and modeling.

And even here, in mountainous, semi-arid Tucson, Russell — an oceanographer, climate scientist and University of Arizona Distinguished Professor of biogeochemical dynamics — is far from alone in her wondering. That’s mostly because she’s right beside UArizona students and faculty, about whom she speaks with enthusiastic praise: “amazing,” “awesome,” “outstanding.”

Russell, who came to the department of geosciences in 2006 after research positions at Princeton University and the University of Washington, holds one of two Thomas R. Brown distinguished chairs of integrative science; Jessica Tierney, also in geosciences, holds the other. Russell regularly welcomes UArizona undergraduates into her lab, offering paid research experience through grants from the National Science Foundation, NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Swimming in this pool of talent, support and spirit, she says, “gives me hope.”

“Everyone’s so worried, so doom and gloom, and this is how we do it,” she says. “This hope, this profound inspiration — from the young who say, ‘Yes, we can. Yes, we will. Yes, we are.’ It is the delight of my life to be here, working at this time with these people to try and change our climate future.”

The biogeochemical Argo floats — about the height of a person, with sensors measuring dissolved oxygen, nitrate and pH — descend more than 1,000 meters into the Southern Ocean, sinking to between 11 and 20 football fields deep. The data is returned via satellites and supercomputers to Russell and her collaborators on the Southern Ocean Carbon and Climate Observations and Modeling project. It helps tell a story, one with a past, present and future: the story of what Russell calls “this climate journey on planet Earth.”

In a College of Science public lecture delivered at Centennial Hall in 2016, Russell noted that “global warming is ocean warming”: The oceans shoulder and reveal the brunt of climate change’s effects. And so Russell — born in Seattle and raised in Kotzebue, Alaska, a fishing village of 3,000 at the edge of the Baldwin Peninsula in Kotzebue Sound — studies our world’s largest bodies of water.

Relentlessly optimistic, she says she’s found “the best place in the world to do this work,” however ironically in the landlocked, often rainless Southwest.

“It actually makes an incredible difference to everything we do to have this unbelievably supportive, loving, extraordinary community,” Russell says. “I never felt it at any university I worked at before. It’s just here.”

A proud champion of Russell’s work is an environmental and community advocate in her own right.

When Sarah Smallhouse and her sister, Mary Bernal, were small, they had a pretty simple life. The Tucson home where they lived, far from fancy, was appointed with utilitarian furniture standardized by their dad for the company he’d co-founded, which applied early transistor technology to new products.

Thomas R. Brown — engineer, entrepreneur, husband, and then father — started the Burr-Brown Corporation in 1956 with his friend Page Burr, a researcher in New York, and his wife, Helen, who built early products alongside him in their garage. Tom and Helen based the company in Tucson because they thought the Sonoran Desert was a beautiful place to live and raise a family.

Helen passed away in 1967, when Smallhouse was 9 and her sister 6. Smallhouse says that thereafter, her father “was kind of like two parents rolled into one.” And even if their childhoods were unconventional and somewhat businesslike, she says, “He was a great father. We loved him so much and miss him deeply.”

Sometimes Tom took his daughters on business trips to visit the company’s international sales offices. He thought it was important to show his daughters life beyond Tucson. “He exposed us as best he could to what he thought we should appreciate about diversity in the world,” Smallhouse says.

No wonder, then, that as president of the Brown Foundations — which support economic education, STEM education and research, civic leadership and workforce development, including through research support and scholarships at UArizona and Pima Community College — Smallhouse’s concerns are global.

“I’m deeply concerned about climate change — understanding it, mitigating it where we can and adapting to it when we must,” says Smallhouse, who chaired the Southern Arizona Buffelgrass Commission for years and currently chairs the Biosphere 2 advisory board.

“How are we going to address the very serious consequences that arise because of rapidly changing conditions?”

And it’s also no wonder that Smallhouse values wholeheartedly the work being done by Russell, whose faculty chair was recently extended.

Of Russell, Smallhouse says, “It is pretty much impossible to be around her and not develop a sense that we’re focused on the right thing, and there’s reason to be aggressive and determined — positive change is possible, and we are figuring out how to make it happen.

“Joellen is contributing something that is very precious indeed,” she continues. “I wish there were thousands of her. But there is just one, so both Mary and I are enthusiastic supporters of her work.”

The mission at Burr-Brown was to “provide something of value to humankind.” The Brown Foundations are perpetuating the legacy of Tom Brown and Burr-Brown through their support of Russell’s work.

Smallhouse says that everyone has a part to play in slowing down global warming and that solutions require us all to embrace our individual roles. As for the part she’s playing, and how her father would see it?

“I think,” she says, “he’d be pleased.”